The first 911 call came in at 4:36 p.m. on August 28, 2019.

“Emergency, we have a man shot in the middle of Clark Avenue,” a woman said. “He’s in the middle of the street. Dying … a man came up behind him in a black hoodie and shot him in the back!”

“Bah-bah-bah-bah-bah-bah-bah!” a man was heard saying on the same 911 call, reenacting the gunfire that had laid down 30-year-old Antonio “Bisket” Parra. A trail of blood and spent shell casings followed Bisket from the sidewalk to the eastbound lane of Clark Avenue on the west side of Cleveland.

An APB went out over the police radio: “Blue Volkswagen, 2006, occupied by two. Black male driver wearing all black.… When the vehicle is located, please detain all subjects in the vehicle and process. Tow the vehicle per homicide. Listed owner of the vehicle’s been located.”

The Volkswagen was named by multiple witnesses as the getaway vehicle for Bisket’s killers. It was found two days later, reduced to a smoldering shell behind the parking lot of an abandoned church in Cleveland’s Kinsman neighborhood.

The vehicle’s owner, Frank Q. Jackson, however, was found just hours after Bisket’s murder at his residence on East 38th Street—the home of his powerful grandfather, Mayor Frank G. Jackson.

“Q.’s at the mayor’s house right now,” one of the would-be arresting officers said into his cell phone as he walked up the driveway. “He just pulled up. [Sergeant] Gomez asked us to detain him. So we’re gonna go up to the door and try to grab him.”

But that evening, Mayor Jackson had a phone conversation of his own with his chief of police, Calvin Williams, who called to inform him that homicide detectives wanted to question his grandson about a murder.

It is unknown what was said on that phone call. But the following facts are clear: Police intended to take the mayor’s then-22-year-old grandson into custody; after confronting the mayor, they walked away without their suspect. They did not question him or administer a gunshot residue test—standard departmental policies for confronting a murder suspect. Little else is known of the encounter because, according to a local news outlet, Mayor Jackson told the officers to turn off their body cameras.

Instead, homicide investigators seemingly settled for Frank Q.’s simple explanation: Frank Q. had sold the car in question months before the murder. But a search of court records revealed that the mayor’s grandson had been ticketed in the car only two weeks before the killing.

A year later, in a civil lawsuit charging him with wrongful death, infliction of emotional distress, and obstruction of justice, Mayor Jackson was asked why police left his house without his grandson. “I do not know,” the mayor responded, “however, to the best of my recollection while outside my house … [police] spoke on the phone with Frank Q. Jackson’s lawyers.” To this day, Frank Q.’s suspected involvement in the crime has not been explained to the public. The murder remains unsolved.

It was not the first time that Frank Q. Jackson had run into trouble with the law. Nor was Frank Q. the only young relative of the mayor who has had run-ins with Cleveland law enforcement. Frank Q. and the mayor’s great-grandson are suspected members of No-Limit 700, a violent street gang that Ward 8 Councilman Michael Polensek told me operates with impunity on Cleveland’s east side. “The rumor is they’re running rip-shod over the Central neighborhood and that the police department is looking the other way,” said Polensek.

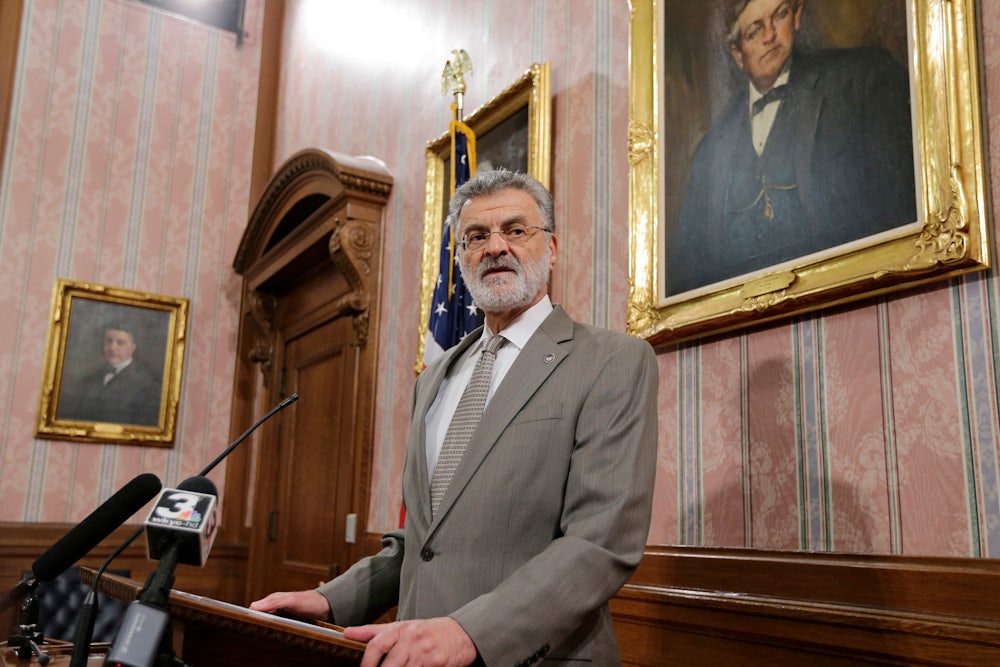

An advocate for Cleveland’s Black and poor going back to his first campaign for City Council in 1989, Frank G. Jackson, now in his seventies with a bushy gray beard and a bouffant of salt-and-pepper hair, built his career as a street populist who saw housing, jobs, and health care as human rights. Born to an African American father and an Italian American mother in the troubled neighborhood of Kinsman, Jackson and his family later moved to Central, where Jackson still lives today, in a modest, vinyl-sided colonial on East 38th Street, among the core constituency that reelected him in 2017 to an unprecedented fourth term as mayor.

In a 1992 profile of Jackson in The Plain Dealer Magazine, the writer Michael Heaton observed that the then councilman of Ward 5 (which includes Central) “abhors the crime, not the criminal.”

“Not many survive the conditions that make up neighborhoods like the ones in Ward 5,” Jackson told Heaton. “That’s why I can’t judge these people. I don’t think I’m in any way superior to them, and they know that.”

But there is now a suspicion in Cleveland that Jackson’s empathy has tilted into outright protection of family members accused of harming the community that the mayor has sworn to protect.

In 2017, when Cleveland Police pulled over Frank Q., then 20 years old, for having a passenger riding in the flatbed of his pickup truck, they say they found another passenger with a Glock 9 mm next to him in the back seat, and yet another passenger who had an arrest warrant for attempted murder. When Carl Monday, a local television reporter, confronted the mayor about the incident, the mayor admitted to personally knowing both the man with the gun and the man with the murder warrant.

“Many times people who run afoul of the law are people that I know and are people who’ve stayed over at my house because they’ve been friends with my grandkids and my great-grandkids,” explained Jackson. “They don’t pull guns on me. They’re respectful to me. I don’t have those kind of issues or concerns with the young people out on the street.”

It was a stunning admission by the sitting mayor of a major American city and, as such, the ostensible head of one of the biggest police departments in the nation. But in Jackson’s estimation, hosting in his home young men who carry guns and are wanted for murder was not a scandal. Rather, it was confirmation of his reputation as the street populist who still resides in his rough-and-tumble Central neighborhood. For Jackson, this was a teachable moment for his city.

“In the environment in which my grandson lives, and where I live, people know each other,” said Jackson. “And they don’t judge them and say, ‘Oh, I think you may have a warrant so I’m not gonna talk to you,’ or, ‘Oh, somebody said you have a gun so I’m not gonna talk to you.’ … It doesn’t work like that on the street.… [My grandsons] live in an environment where [guns are] prevalent.… So if many of the kids have guns … they are gonna have friends who have guns.

“I wish the world was Pollyanna,” the mayor added. “I wish that Disneyland prevailed. And I wish that the illusion that people think the world is, I wish that were reality. But it’s not.”

About two months later, after Frank Q. was pulled over yet again, police say they found a .40 caliber Glock handgun in the center console. When asked if he had anything illegal on his person, the mayor’s grandson replied, according to the police, “Yeah, I have a clip in my pocket.”

This time, Frank Q. was charged with felony gun possession, resulting in Mayor Jackson striking a more evasive posture with reporters. “This is a family issue that is both deeply personal and painful,” he said in a statement, refusing to answer any questions in person. And in the spring and summer of 2019, as his grandsons’ alleged crimes became more violent, Mayor Jackson began to retreat altogether from the press.

While Frank Q. enjoyed the privileges of being the mayor’s grandson, the young man who bled out as Frank Q.’s car sped away had a very different path. Bisket Parra wrote fiction. One eerie passage seemed to foretell his death, right down to the number of bullets that would pierce his body and his age when he met his end: “Damn this hurt! I can feel my spirit drift from my body as I lay on the ground. My life’s essence leaving as it flows rapidly out of the seven holes left by the gunshots.” Parra also drafted essays on love, power, time, and money, and his social media presence was inflected with a philosopher’s wit.

“You can never put bullshit in the game and expect a blessing in return. Period,” Parra spoke into his smartphone for one Facebook post.

“Bisket was different,” Parra’s niece, Aariana Germany, told me, calling him by the nickname he received at birth when his father noted that “his breath smells like biscuits.” She recounted how her uncle would sit in the middle of her grandmother’s living room floor in a classic yogi’s pose—legs crossed, palms facing upward with thumbs and middle fingers touching—and meditate for up to an hour.

Still, street life beckoned. In 2009, Bisket robbed a drug dealer by tapping the muzzle of a .45 caliber handgun on his chest. Compounded by previous weapons and drug charges, the stick-up resulted in Bisket, then just 20 years old, spending the next six years of his life behind bars.

Upon his release in 2015, he returned to his old haunts on Cleveland’s predominantly Black east side. His Facebook history offers insights into his homecoming. There’s the photo showing off new clothes: docksiders, red chinos, an untucked white button-down draped over a slender 5-foot-9 frame. Sunglasses and a checked tie. There’s a photo memorializing Bisket’s reunion with his daughter, who was born the year he entered the state prison system.

Then frustration sets in as that first autumn of freedom turns to winter. “Sometimes we are the person holding ourselves back from greatness,” reads one post from just before Christmas.

According to Andrea Parra, Bisket’s mother, this was when her son started exploring a drug deal with a friend who had ties to No Limit-700. Bisket had a proposition for the 700s: His uncle, a purported player in the Mexican border town of Nuevo Laredo (a lucrative drug corridor), could deliver large quantities of drugs. Members of the 700s liked what they heard, according to Andrea, and gave Bisket $40,000 to travel to Nuevo Laredo and return to Cleveland with some weight.

The trip is partially documented on Bisket’s Facebook: There’s a selfie taken inside a cantina, where a woman with long brown hair and a cigarette dangling from her fingers kisses Bisket’s cheek. “Boy don’t do like your uncle come home with a Mexican baby lol,” chides Bisket’s mother in a comment on the post.

Bisket returned home in the early spring of 2016—without the product he’d promised to the 700s, and without their $40,000. According to Andrea, Bisket’s uncle claimed he was robbed of Bisket’s buy money. Upon returning to Cleveland, Bisket confessed the misadventure to his father, who understood the trouble his son was now facing. So he and some other relatives pooled together some money to present to the 700s. “But it just wasn’t good enough,” Andrea told me.

The first attack came on July 8 of that year, just after midnight at the corner of East 40th Street and Quincy Avenue—two blocks from the mayor’s house. According to the police report, three to five shots were fired. Bisket looked down and realized he was bleeding from both legs.

The shooters, two Black males dressed in black, sidestepped Bisket and absconded with his rented Rav 4. Police later glimpsed the two perpetrators ditching the car on East 40th Street. The police lost sight of them but found they’d left behind a 9 mm semiautomatic, which was linked by DNA test to Matthew Kimmie, a.k.a. Fatt Matt, a 15-year-old connected via Facebook to the mayor’s grandsons and other suspected members of No Limit-700.

Ultimately, a Cleveland police detective closed the case without any arrests due to Bisket’s refusal to cooperate. Besides, the detective’s prime suspect, Fatt Matt, was dead—killed during a home invasion gone awry.

Bisket eventually recovered from his wounds, but the shooting weighed on him heavily. “It made me more so pessimistic about a lot of things,” Bisket would later recall. “It gave me a different perspective on life, and it kind of closed me down.”

The Jackson family’s troubled 2019 started on the evening of May 17, when Frank Q. and four other suspected members of No Limit-700 were cruising in Frank Q.’s pickup truck with a couple of guns and live ammo, according to court documents. Near the intersection of East 55th Street and Quincy Avenue, they pulled onto a small side street and set upon two juveniles.

“[My nephew] thought somebody was doing a drive-by,” said the woman who called the police. But instead of blood, flecks of Dayglo-blue paint dotted the gray asphalt. “Scared, afraid, terrified [at] the thought they was about to get shot with a real gun,” said the woman, “but it was a paintball in his side and his back and leg.”

An APB went out, and a patrol car quickly spotted Frank Q.’s pickup on Quincy Avenue, just a block from the scene. When police initiated a stop, three of the young men fled on foot, but Frank Q. was detained, according to court documents. Police searched the pickup and say they discovered drugs along with a paintball gun and the two semiautomatic handguns, for one of which Frank Q. had a concealed-carry permit—apparently a lesson learned from the felony gun charge he skated on two years before.

“Ah shit, I should have told you guys about that,” he said to the officers. As for who owned the other gun, Frank Q. said he didn’t know.

Less than a month later, on June 10, while Frank Q. was out on bond for charges stemming from the paintball gun incident, multiple witnesses say they saw him brutally beat an 18-year-old woman—Frank Q.’s sometime paramour, Delilah Swift.

In a photo submitted as evidence for the police report, there’s a bruise above Swift’s left eyebrow and a single teardrop seemingly frozen atop her left cheekbone. There’s an abrasion on her right elbow. Bruising on her left knee where Frank Q. hit her with a metal trailer hitch. Dirt streaking her yellow sweatpants from him dragging her around by the hair. “Frank slammed her to the ground,” said a witness. “He almost put her to sleep.”

While Swift was giving her own account to police at the scene, Frank Q.’s pickup reappeared. The occupants threw the vehicle into reverse and fled. The police did not give chase but perhaps more disturbing for Swift—who told officers, “I’m so scared” and “I want to go inside”—was the vehicle she identified as belonging to Frank Q.’s mother, filled with members of the Jackson family, circling the area as Swift continued talking to the officers. She told the police she feared the Jackson family would harm her once the officers left.

The following month, on July 17, it was the mayor’s great-grandson’s turn to grab headlines. A close nephew of Frank Q.—“I’ll go to war for him,” his uncle declared on Facebook—the then 16-year-old was charged with involvement in an attempted drive-by shooting of a Cleveland police officer, according to court documents. (The New Republic is not naming Jackson’s great-grandson because his alleged crimes were committed when he was a minor.)

It was nearing midnight and Gang Unit Detective Michael Harrigan was pursuing a man whom police first encountered drinking with a large group in the middle of East 86th Street near Quincy Avenue. Upon seeing the police, the man allegedly tossed a gun, ran into a house, jumped out of a back window, and took off through a backyard toward East 84th Street.

Harrigan was attempting to circle the block when he encountered a young man he would later identify as the mayor’s teenage great-grandson, driving a dusty gray sedan with a fellow suspected gang member riding shotgun. “I was coming down 86th, and they almost T-boned me, and they started popping off rounds,” Harrigan said over the police radio.

In court, the detective said he heard a gunshot as the two vehicles nearly collided. Looking back, he saw Jackson’s great-grandson had stopped the car; his companion had gotten out and fired two more shots in his direction.

Only five days later, on July 22, Frank Q. appeared in municipal court for the paintball-gun incident. Cleveland City Prosecutor Karrie Howard said Frank Q. Jackson was a “great candidate” for drug court—a diversion program offering drug counseling in lieu of prison. But Frank Q. had already been in a diversion program. And the Delilah Swift case—which Howard had somehow failed to press charges on—was still hanging in the air.

“And I’d just like to add that if his name was Joseph Edwards, we would be standing here doing the exact same thing,” Howard told the judge. “There is no preferential treatment.”

Meanwhile, Bisket was preparing to finish up his second stint in prison. He had received a three-year sentence for having a weapon under disability and improperly handling a gun in a motor vehicle, charges that stemmed from him fatally shooting a man who had attacked him in 2017 in Barberton, Ohio, less than an hour’s drive south of Cleveland, just outside Akron. The jury believed his claim that he had been acting in self-defense, acquitting him of murder charges. “I regret that the situation happened,” Bisket said in court. “I really wouldn’t intend to just, like, kill somebody.… I’m not even that type of person by nature.”

As he neared his release, he confessed he was wary of returning to the streets. “I’m scared to come home,” Bisket told his niece, Aariana Germany, during a phone call from prison in late July 2019.

“Why?” asked Germany.

“Because I don’t know who’s after me,” said Bisket. “I don’t know who family feel a type of way.”

“But he knew someone was after him,” Germany told me through tears. “Even when you in jail, the streets talk.”

Upon Bisket’s release from prison, he resolved to leave the street life behind. Bisket planned to pursue a career in real estate. “My little brother came home with a different state of mind,” Anthony Billups, Bisket’s oldest brother, told me. “I’m still in the streets, and he’s telling me, ‘We gotta do something different.’ He was changing the family. He was showing us that there’s other shit than the street.”

In the afternoon of August 28, 2019, less than a month after his release from prison, Bisket called his mom with some good news.

“I got a job,” he said. “Zanzibar, an upscale soul food restaurant downtown.”

“I’m proud of you, son,” said Andrea.

“Gonna go buy some new shoes and clothes for my first day,” said Bisket, before heading to the Urban Thrift, a second-hand clothing store on Clark Avenue at the corner of West 51st Street.

According to his mother, who had heard through her own contacts on the street, her son was lured to the Urban Thrift by so-called friends who had allied themselves with one of the 700s Bisket owed money to.

Hours later, Bisket was dead. As Cleveland police officers walked up the driveway to Mayor Jackson’s house, one of them spotted a young man in a pickup truck. “I promise I would not come to the mayor’s house and cause a disturbance unless I had good reason,” the officer told him, according to bodycam footage.

On October 7, 2019, less than six weeks after Bisket Parra was murdered and Cleveland police walked away from the Jackson household without their suspect in hand, Mayor Frank Jackson took to the podium on the stone steps of Cleveland City Hall. It was just after Ward 2 Councilman Kevin Bishop implored the public to abandon a central code of the street: “The ‘no snitch’ rule,” the councilman said with exasperation. The presser was not in reaction to Bisket’s murder alone but to a wave of violence that culminated in the senseless killing of Lyric Melodi Lawson, a six-year-old girl whose clapboard house in the city’s predominantly Black and poor Collinwood neighborhood had just days before been sprayed with bullets while she slept in a bed with her cousins.

Jackson declined to echo the councilman’s straightforward plea for a witness to step forward. Instead, he offered platitudes about community involvement, then argued that violent crime is a symptom, not the cause, of the underlying social and economic conditions plaguing Cleveland’s mean streets. “And we want to also address that as a city, and invest in those programs that help children who are on the edge, that could go either way,” he said.

Jackson’s familiar interventions on behalf of Cleveland’s troubled young men rang hollow on that October day. His great-grandson was in juvenile detention, awaiting trial for charges that included a first-degree felony for shooting at a cop (he is currently under house arrest and still awaiting trial). Frank Q. Jackson was now a suspect in Bisket’s murder.

Polensek, the councilman for Ward 8, told me he does not believe the mayor had done anything wrong. “Look, there are many of us on council who, like Frank, are living in the same rough neighborhoods that we grew up in,” said Polensek, a Slovenian American who was raised in Collinwood, not far from where Lyric Melodi died, and still resides there. “There are many of us whose families have been affected by crime and/or bad behavior by some members of our families. That’s the reality of living in a poor urban area. But I’ve served with Frank a long time, and based on the individual that I know, I can’t conceive that he would be a part of anything illegal, or any illegal cover-up.”

But at the presser for Lyric Melodi Lawson, there were others on council who appeared to blame the mayor for Cleveland’s spike in violent crime, or at least for tacitly endorsing the code of silence that allowed the violence to run unabated.

“If you know something about these vicious and violent crimes … speak up,” Councilman Hairston said forcefully into the microphone. “You are just as bad as the folks who’ve committed these crimes if you stay silent and stay quiet.” And as if he were speaking directly to Mayor Jackson, who was standing less than 10 feet away, the councilman concluded: “Those who are listening to us, please, encourage someone that you may know, even if you don’t know something, to ask them to come forward.”

In the nearly two years since Bisket Parra’s death, Mayor Jackson has remained silent on his grandson’s suspected involvement, and the murder remains unsolved. But a look back at the mayor’s public comments on youth violence suggests that Jackson’s behavior is in keeping with a worldview that sees both Black crime victims and Black perpetrators of crime as the unfortunate casualties of systemic and structural racism.

“Whenever you have these kinds of situations, you should look behind the curtain also, and look into the lives of the individuals, and look into what has brought them to this point,” said Jackson in the 2018 interview with Carl Monday. “Many of the young people … they have significant challenges. They don’t have employment. They’re constantly under pressure because of the threat of maybe some other group, or some other street, or some other location.… They’re constantly under the threat are they gonna be harmed.”

But Peter Pattakos, a lawyer for the Parra family, sees Jackson’s behavior another way. “You spend so many years in power and you get desensitized to your own abuses of it,” said the 42-year-old trial lawyer. “Jackson is captured by corporate cash. He’s got one foot in one Cleveland and one foot in the other Cleveland. The mayor in part holds power on his purported representation of the poor people in the inner city, but his family is above it, and it’s created this spectacular mess.”

On behalf of Andrea Parra, Pattakos is suing the mayor and police chief for obstruction of justice and for creating an environment that permitted Frank Q. Jackson and his associates to allegedly commit a series of increasingly violent crimes over the spring and summer of 2019, resulting in Bisket’s murder. “Andrea Parra has every reason to believe that her son would be alive today if it weren’t for the mayor’s efforts to cover up for his grandsons’ crimes,” said Pattakos. Mayor Jackson denies the suit’s claims, and did not respond to a request for comment.

In 2021, as Jackson continues to mull a run for an unprecedented fifth mayoral term, Pattakos expects to depose the mayor and the police chief sometime before the November election. And of Cleveland’s incestuous legal community, which has dismissed his lawsuit against the mayor as highly unusual and “almost impossible,” Pattakos is unforgiving.

“What looks like such an egregious use of power, that there could be no remedy for that,” said the lawyer. “It just says a lot about the way the law in Cleveland has moved in favor of the powerful. These people are supposed to be guardians of the law. They’re supposed to shine light so that the powerless are not so powerless against the powerful. Instead, they’re clutching their pearls at the idea that Andrea Parra can recover something.”

In the meantime, Andrea Parra and her family continue to grieve Bisket’s death. In the early evening of August 28, 2020, on the anniversary of her son’s passing, she gathered roughly 30 friends and family members on the sidewalk in front of the pandemic-shuttered First Class Barbershop at the corner of Clark Avenue and West 51st Street—where Bisket took his last breaths. As the rain poured down, the mourners drank Patrón from red plastic Solo cups and huddled underneath black umbrellas and red and blue helium balloons.

“I just wish someone would step up and give us some justice,” she said.