The House on Friday morning approved President Joe Biden’s massive social spending bill, representing a historic investment in health care, childcare, climate, and education and bringing the legislation one step closer to becoming law. That the House managed finally to bring this bill to the floor and pass it is a significant achievement for Democrats—the measure has been the subject of intense negotiations that have burdened it with substantial delays. But Democrats should wait to break out the champagne, as this key part of the president’s legislative agenda now faces a complicated path forward in the Senate.

The House passed the nearly $2 trillion bill, known as the Build Back Better Act, along party lines, as it faced stiff resistance from Republicans who have decried the measure as an irresponsible spending spree. Democrats have a narrow majority in the House and could only afford to lose three votes. The bill passed 220 to 213, with all Republicans and only one Democrat, Representative Jared Golden, voting against it. Democrats celebrated the passage of the bill with cheers and applause, chanting “Build Back Better.” It now heads to the Senate, where it is almost certain to be altered, meaning that the legislation passed in the House will be far from its final form.

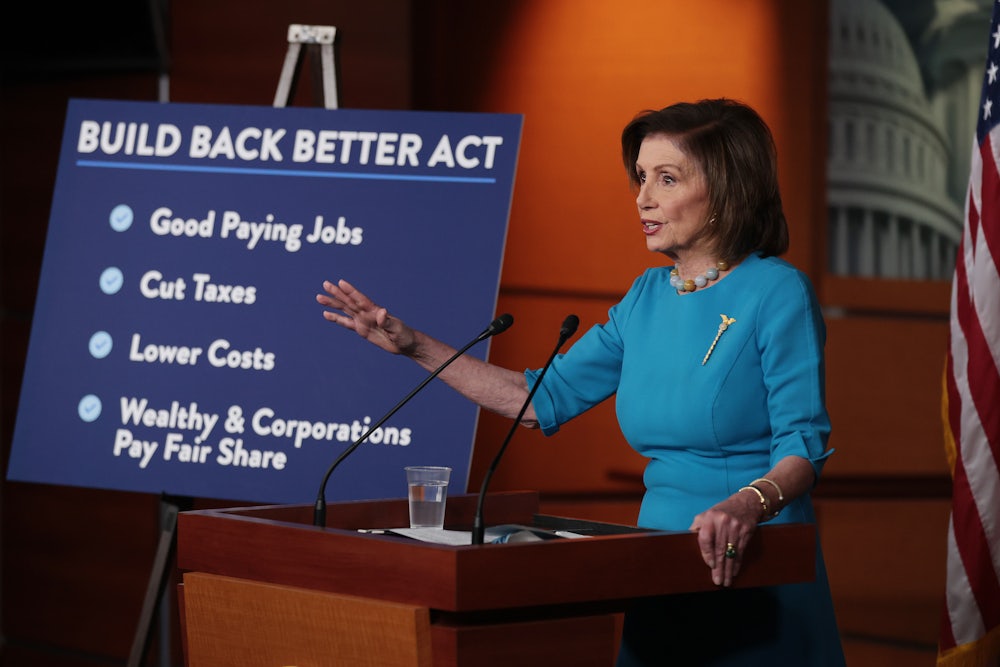

In a speech before the vote, Speaker Nancy Pelosi called the bill “historic, transformative, and larger than anything we have done before.”

“We, this Democratic Congress, are taking our place in the long and honorable heritage of our democracy with legislation that will be the pillar of health and financial security in America,” Pelosi said in a speech punctuated by frequent applause from Democrats. The speaker wore a vibrant white pantsuit, her color of choice for many moments she deems historic in the House.

Biden, in a statement, touted the bill’s key provisions, saying that the Build Back Better Act “puts us on the path to build our economy back better than before by rebuilding the backbone of America.”

“For the second time in just two weeks, the House of Representatives has moved on critical and consequential pieces of my legislative agenda. Now the Build Back Better Act goes to the United States Senate, where I look forward to it passing as soon as possible so I can sign it into law,” Biden said, referring to the passage of the bipartisan infrastructure bill two weeks earlier.

The hours leading up to the House’s ultimate vote were not clear of procedural hurdles. House Democrats had waited to schedule a vote on the bill until this week, anticipating a score from the Congressional Budget Office, which estimates the cost of legislation. Several moderates had resisted voting on the Build Back Better Act until the CBO had released its score, even though the White House and the nonpartisan Joint Committee on Taxation had already released their cost estimates. This resulted in the vote earlier this month on the bipartisan infrastructure bill, with support from some Republicans offsetting opposition from six progressive Democrats. (For her part, Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez told reporters that she believed her “no” vote had “contributed to the pressure and urgency of this vote tonight.”)

The CBO estimated that the bill would add $367 billion to the deficit over 10 years, but this did not include the expected offset from increased funding for the IRS to crack down on tax cheats. The CBO found that IRS enforcement would generate $207 billion in revenues, but the Treasury Department believes that this is an underestimate.

“I’m glad that we were able to do it in a transparent way that allowed all members, as well as the American people, to see what was in the bill, how much it costs, and make reasonable decisions … in order to advance it,” said Representative Stephanie Murphy, one of the key moderate holdouts who had wanted to see a CBO score before voting, on Friday.

House Democrats had also awaited the results of a “privilege scrub” by the Senate parliamentarian, which despite its name is not a fancy spa treatment but an assurance that the legislation conforms to the rules of budget reconciliation and will therefore not be subject to a filibuster in the Senate. Democrats must use the complicated and arduous process of reconciliation to pass the bill by a simple majority, as it will not receive any support from Republicans. Democrats have a razor-thin 50-seat majority, so the bill must be passed in this fashion, with every Democratic senator on board with the legislation.

The House implemented some “technical changes” after the privilege scrub so that the bill would “comply with Senate procedural requirements.” Lawmakers then voted on a second rule for the bill, setting up a final vote that was originally intended to take place on Thursday evening but got pushed to Friday morning after House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy delayed the vote with a speech that lasted more than eight and a half hours.

The bill includes some of Democrats’ key priorities and is funded by several tax changes, including a new 15 percent corporate minimum tax on large corporations, a tax surcharge targeting the wealthiest Americans, and increased funding for IRS enforcement.

The scope of the bill is massive, with far-reaching policy impacts that are difficult to summarize in a few paragraphs. It represents an ambitious effort to ease the financial strains felt by families, through provisions such as universal, free pre-kindergarten and lowering childcare costs for families earning under a certain threshold. It also extends the expanded, refundable child tax credit by one year. The Build Back Better Act addresses higher education, as well, increasing the maximum Pell grant and boosting funding for historically Black colleges and universities.

The bill dedicates more than $550 billion to combating climate change, including expansion of tax credits for consumers and incentives for companies to transition to clean energy, as well as additional financial incentives to make wind turbines and other equipment in U.S.-based and unionized factories. It also creates a Civilian Climate Corps, employing young people to restore and preserve forests and wetlands.

The health care provisions represented a point of contention in negotiations, and the result is more modest than what Biden initially proposed. However, the White House predicts it will extend coverage to millions of people. It includes an extension of expanded premium subsidies for people who buy health plans through the Affordable Care Act and expands Medicare to include hearing benefits. It also expands coverage for low-income Americans living in states that have not expanded Medicaid, by allowing them to purchase ACA health plans without a monthly premium.

Other provisions include $150 billion each for affordable housing and for home-based care for the elderly and people with disabilities, although the funding for both was cut drastically from Biden’s initial proposal. One controversial measure concerns the state and local tax, or SALT, deduction, a particular priority for Democrats based in coastal states with high property taxes. The House bill increases the deduction from $10,000 to $80,000 through 2026 and imposes a new cap in 2031. According to a recent analysis from the Tax Policy Center, however, the tax cut will primarily benefit the wealthy—an ironic twist, given that Democrats have argued that the richest Americans need to pay their fair share. It is the second-most expensive provision in the bill, behind universal pre-kindergarten and affordable child care.

Democrats had initially hoped to pay for the Build Back Better Act by raising taxes on the wealthy and on corporations, a proposal resisted by Senator Kyrsten Sinema. Some Democratic senators had also proposed a billionaires tax to pay for the bill, but that idea quickly fell by the wayside. By increasing the SALT deduction, Democrats may accomplish the opposite of their initial goal of raising taxes on the wealthy. Golden cited the increased SALT deduction as his reason for voting against the bill, noting its high cost.

The initial bill considered by the House amounted to $3.5 trillion, meaning that some programs were trimmed to shave costs, and some provisions were excised entirely, such as a proposed expansion of Medicare coverage to include dental and vision care, as well as two years of free community college.

Some measures that were initially excluded from a framework proposed by the White House in late October were reincorporated after last-minute negotiations, including a proposal to allow Medicare to negotiate lower prescription drug prices, and four weeks of paid family and medical leave.

Many of the programs are also scheduled to expire within a few years, a cost-cutting measure that risks creating a cliff for people relying on benefits if they are not expanded.

It also obscures the real cost of the bill, as Democrats hope these programs, once implemented, will be extended permanently—a significant gamble, if Republicans regain control of Congress. Republicans have repeatedly shown their disdain for the bill, with McCarthy on Thursday saying it shows how “irresponsible and out of touch” Democrats are. “Never in American history has so much been spent at one time,” McCarthy said, toward the beginning of a rambling speech riddled with mischaracterizations. (The CBO estimates for the cost of the Build Back Better Act are lower than the cost of the 2017 Republican tax cuts.)

McCarthy’s speech outpaced a previous record set by Pelosi in 2018. He was able to undertake the House version of a filibuster with his “magic minute,” which allows party leaders to speak for as long as they want during debate. Although most Democrats departed for the evening shortly after midnight, McCarthy continued to speak for roughly five more hours, in a polemic intended to rally Republicans around his leadership after a difficult two weeks for the party. The Republican leader had received criticism from his right flank after 13 Republicans voted for a bipartisan infrastructure bill negotiated by several GOP senators, and Representative Paul Gosar was censured and removed from his committees on Wednesday after posting an anime video depicting him killing Ocasio-Cortez.

The bill passed in the House is destined to change in the Senate. It will be subject to a “Byrd bath” in the upper chamber, in which the Budget Committee determines whether any of the provisions in the bill violates the Byrd rule. This rule, named for the late Senator Robert Byrd, requires that each provision has a budgetary effect and does not increase the deficit past 10 years.

Some provisions in the House bill, such as immigration reform, are not expected to survive the Byrd rule. The CBO found on Thursday that the provisions related to immigration reform exceeded the allocation provided for them in the budget resolution, which laid out instructions for drafting the reconciliation bill. But the House did not change the immigration provisions ahead of its vote on Friday, meaning that if lawmakers modify the bill to bring the cost down in line with resolution instructions, it will happen at the Senate stage—or the Senate may throw out that measure altogether.

The Senate parliamentarian had previously offered the opinion that a provision on immigration could not be in reconciliation legislation under the Byrd rule. (The parliamentarian can be overruled, but that would require 60 votes, which is not in the cards. The presiding officer could also ignore the parliamentarian’s advice, but this would mean changing rules and precedents without a vote, which is on the whole not great.)

Democratic leadership downplayed the possibility of changes in the Senate after the vote. “We’ve done what we think we can do. The Senate will do what it’ll think it can do. And we’ll come together on behalf of the American people and try to have a coordinated approach as we go off into the future,” Majority Whip Jim Clyburn said.

But beyond the vicissitudes of the budget reconciliation process, the bill will need to be changed to ensure that it has support from all 50 senators, and one in particular: Senator Joe Manchin, who has remained skeptical about the bill and its price tag. The provision on paid leave is likely to be dropped due to Manchin’s opposition, despite the U.S. being the only wealthy country in the world without a national paid leave program. Manchin has raised concerns about the effects that passing the bill could have on inflation, meaning that even more programs may be removed from the final product to ensure his vote. (Economic experts have said that the bill will have little effect on inflation or that it would ease inflation.) Manchin said on Thursday that he had not decided how he would vote on the Build Back Better Act, and added that the vote in the House would not influence his choice.

While House Democrats are optimistic about the future, there’s a general awareness that the fight to pass the Build Back Better Act is far from over.

“I’m hopeful. But I’m also resolved that we have a lot of work today on behalf of the American people,” said Representative Steven Horsford.

This is a breaking news story and has been updated.