The holiday season provides an opportunity to connect with family and reflect on the future. For members of Congress, that can often mean deciding whether to run for reelection, a determination that has particular weight this year, ahead of what is expected to be a bruising midterm election for the Democratic Party.

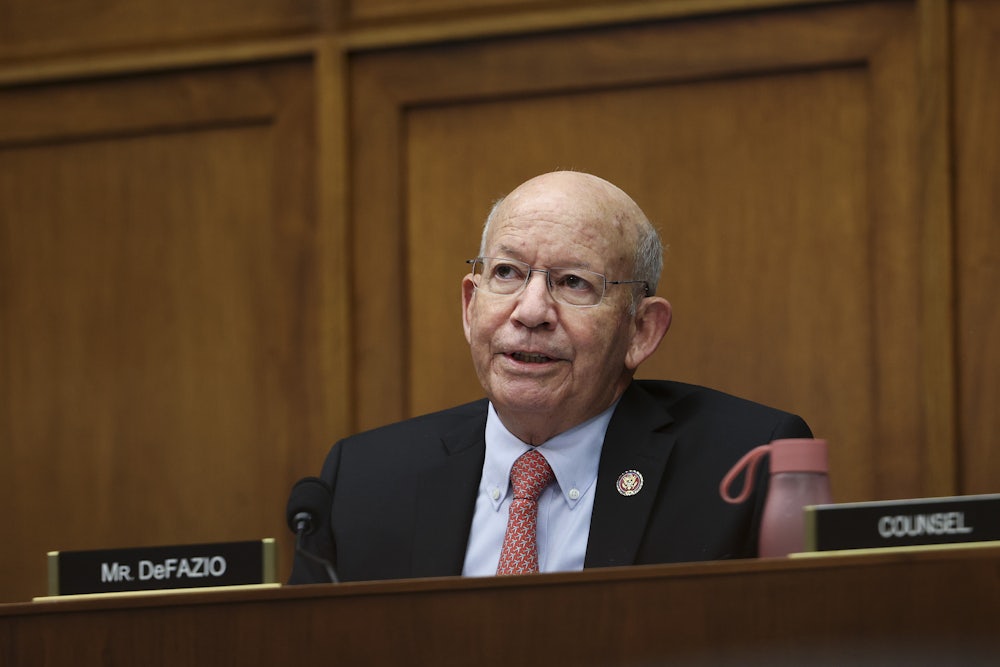

Representative Peter DeFazio last week became the nineteenth House Democrat this year to announce that he would not be seeking reelection in 2022. He is unlikely to be the last Democratic lawmaker to make a break for the exits ahead of the elections. There is a good chance that Democrats will lose their House majority in the midterms, and no one enjoys being in the minority. “If there is a belief that Democrats are going to lose the majority in the House, even if it’s only for two years—being in the minority in the House is a drag,” said Jim Kessler, a longtime Democratic strategist and the executive vice president for policy at the center-left Third Way think tank.

Historically speaking, the party in power tends to do poorly in the first midterm after a presidential election. Democrats famously experienced a shellacking in the 2010 midterms, and Republicans were overwhelmed by a blue wave in 2018. In the last 100 years, the president’s party has picked up seats in the first midterms after a presidential election only three times: in 1934, 1998, and 2002.

Moreover, the 2022 elections will occur after redistricting, in which state legislatures redraw congressional maps based on new census data. Partisan redistricting is common, meaning that already vulnerable Democrats in GOP-controlled states may suddenly find themselves defending a seat that has been redrawn to be more safely Republican.

“Retirements are common, especially in a redistricting year,” Representative Sean Patrick Maloney, the chair of the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, told The New Republic. He noted that the number of Democrats retiring in 2022 was—at least for now—still lower than the 26 Republican members who did not seek reelection in 2020. Thirteen Republicans have also announced that they will not seek reelection in the House this year, with eight of them running for another office.

Representative Hakeem Jeffries, the chair of the Democratic Caucus, agreed that retirements in a redistricting year are nothing unusual. “I believe that we’re not even close to being on pace to hitting that number that we were at in 2012,” Jeffries said, referring to the last year which saw the electoral map reshaped by redistricting, in which 22 Democrats retired. “I think we’re on track to hold the House.”

Because of the coronavirus pandemic, redrawn maps have been revealed at a later point in the cycle than is typical, meaning that there is even greater uncertainty as to what the elections will actually look like. “The 2022 midterm is going to be one of the most volatile and unpredictable of any recent cycle,” said Steve Israel, a former congressman who served as the chair of the DCCC during the 2012 and 2014 election cycles. He added that the combination of redistricting and retirements would create a major headache for campaign committee leaders of both parties. “Both committees are dealing with both at the same time, and that just creates a highly uncertain environment, and it also puts districts into play later than ever,” Israel said.

Both parties have long taken advantage of redistricting to draw maps in their favor, which affects members of both parties. In California, Republican Representative Devin Nunes announced his retirement after early draft maps showed him in a new district. Republicans nevertheless have the edge this year, as the GOP controls more state legislatures. This could result in a shift of several seats to Republicans, which could grant them the majority even if Democrats held onto every seat they are currently defending. (The Justice Department has sued to block Texas’s updated congressional map, arguing that it disenfranchises Black and Latino voters in violation of the Voting Rights Act.)

“Redistricting probably is a net loss for Democrats of about five seats,” Kessler estimated. “The trend so far in redistricting has been to make pink seats red and light blue seats blue and have fewer purple seats, and occasionally steal a seat from the other party if you can be opportunistic in a handful of states.”

There’s no universal reason for why members choose to retire, although redistricting is not an unimportant consideration. Representative Filemon Vela of Texas, who announced he would not run for reelection in March, would have had to defend his seat in a district that has gone from Democratic to leaning Republican under the redrawn map.

But many of the members not seeking reelection are in solidly Democratic seats that are unlikely to flip, while others are just seeking new opportunities. Of the 19 incumbents not seeking reelection, eight are running for another office. Representatives Tim Ryan of Ohio, Conor Lamb of Pennsylvania, Val Demings of Florida, and Peter Welch of Vermont are running for Senate in their respective states. Representatives Tom Suozzi of New York and Charlie Crist of Florida are each running for governor, and Representative Anthony Brown is also seeking statewide office with his campaign for Maryland attorney general. Representative Karen Bass is aiming to be the next mayor of Los Angeles.

DeFazio, who chairs the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee, is one of three respected committee chairs retiring at the end of their term. Representative John Yarmuth, who chairs the Budget Committee, and Representative Eddie Bernice Johnson, chair of the Science, Space and Technology Committee, have also announced they will not run for reelection. DeFazio and Yarmuth are both septuagenarians, and Johnson is 86. (Johnson’s Dallas-area district is set to remain solidly blue after redistricting.) Several of the other representatives who have announced their retirements are over the age of 70, retirement age in any other industry.

“It’s time for me to pass the baton to the next generation so I can focus on my health and well-being,” DeFazio said in a statement announcing his retirement last week. “This was a tough decision at a challenging time for our republic with the very pillars of our democracy under threat, but I am bolstered by the passion and principles of my colleagues in Congress and the ingenuity and determination of young Americans who are civically engaged and working for change.”

Arguably, this term in Congress would be considered a capstone in many lawmakers’ careers: Democrats are still on track to pass the Build Back Better Act, a massive public investment act. Additionally, they have already passed a large bipartisan infrastructure bill. With the winds of fortune blowing against Democrats in the 2022 midterms, why not go out on a high?

But some Democrats believe that getting these bills passed will help them in the midterms. “I think that they’re going to see over the course of the next 689 10 months, the implementation of these bills that we have passed that are generational investments, and I’m optimistic we’re going to do well,” said Representative Madeleine Dean.

Atmosphere may also help to account for the recent exodus. It would not be an exaggeration to call the House of Representatives a hostile work environment. On January 6, members of Congress saw their place of work literally invaded by insurrectionists, a traumatic experience that fomented mistrust between those who supported the goals of the siege—overturning the presidential election—and those who were implicitly or explicitly targeted by the rioters. In the months since the insurrection, many House Republicans have sought either to downplay the violence of the day or to deny it altogether.

“I think January 6 and the resulting tensions have factored into the deliberations of many members,” Israel said.

The mutual suspicion has been further exacerbated by increasingly toxic partisanship and a willingness to target colleagues of the opposite party in personal or even discriminatory terms. Republican Representative Paul Gosar was censured and stripped from his committees in November after he posted an anime video to Twitter depicting him killing Democratic Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, and GOP Representative Lauren Boebert has come under fire for making anti-Muslim remarks about Democratic Representative Ilhan Omar.

Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy has privately urged his conference to remain unified but has not publicly condemned his most stridently right-wing members. In just over a year, McCarthy might be well on his way to being the next speaker of the House, and he will need the support of all members of his conference to accomplish that goal. In his eight-and-a-half-hour marathon speech last month, McCarthy warned that Democrats would face retaliation for removing Gosar and, earlier this year, Representative Marjorie Taylor Greene from their committees if Republicans retake the House.

“With colleagues right now whom you can’t trust, who do things that are in many ways offensive, that makes it very difficult,” Yarmuth told The New Republic. “You’re walking on eggshells a lot of the time, trying to, you know, ‘Should I say hi, should I be friendly, when I really despise everything about this person and everything he or she stands for?’”

Along with this “toxic” environment, Yarmuth said, there is a frustration with the Senate as a “totally broken institution.” Even though they currently hold the majority in the Senate, Democrats are unable to pass several of their priorities because they do not have the votes to overcome a Republican filibuster. Bills that have passed in the House to restore a provision in the 1965 Voting Rights Act gutted by the Supreme Court, to codify abortion rights into federal law, and to establish equality under the law for LGBTQ Americans have foundered in the Senate.

“When you really work hard to do what you think is good legislation, and are able to get it through the House, which is no mean feat, and then it just sits there in the Senate—why are we here?” Yarmuth said.

Against this backdrop, it is easy to see how people could become disenchanted with serving in the House. But Democrats remain at least publicly hopeful that the midterms will not witness staggering losses. Maloney told me that he believed the effect of Democratic retirement announcements had been “overstated.” “It’s not going to determine the outcome of the election,” he said.

Kessler said that he believed there was “more cause for optimism” than in 2010 or in 1994, the first midterm election after President Bill Clinton took office. In those years, there was a far higher number of conservative Democrats in districts that had become ruby red. “Democrats were holding lots of seats that, by that point, had really ceased to be Democratic territory,” Kessler said. Just seven Democrats currently represent districts that former President Donald Trump won in 2020, and of those, only Representative Cheri Bustos has announced she will not seek reelection in 2022. (There are plenty of pickup opportunities for Republicans in districts that only narrowly went for Biden, of course, particularly with the pendulum swing of party support factored in.)

It’s likely that there will be more retirement announcements in the coming weeks and months, but whether that portends doom for Democrats in the midterms is yet to be seen. President Joe Biden’s approval ratings, which are currently in dire straits, are likely to be key in determining whether Democrats hold or lose the majority in both chambers.

“If it stays where it is now, it’s bad news,” Kessler said about Biden’s low popularity. “But we’ve got 11 months between now and the election.”