The First Amendment sets forth two requirements for the government when it comes to religion. On one hand, it “shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion,” which is known as the Establishment clause. Nor shall it pass a law “prohibiting the free exercise thereof,” which is called—you guessed it—the Free Exercise clause.

What happens when these clauses are in tension with each other? In Tuesday’s decision in Carson v. Makin, the Supreme Court effectively said that the Establishment clause must typically give way to the Free Exercise clause. The 6-3 ruling, which fell along the usual ideological lines, struck down a Maine law that limits its tuition-assistance program to “nonsectarian” schools.

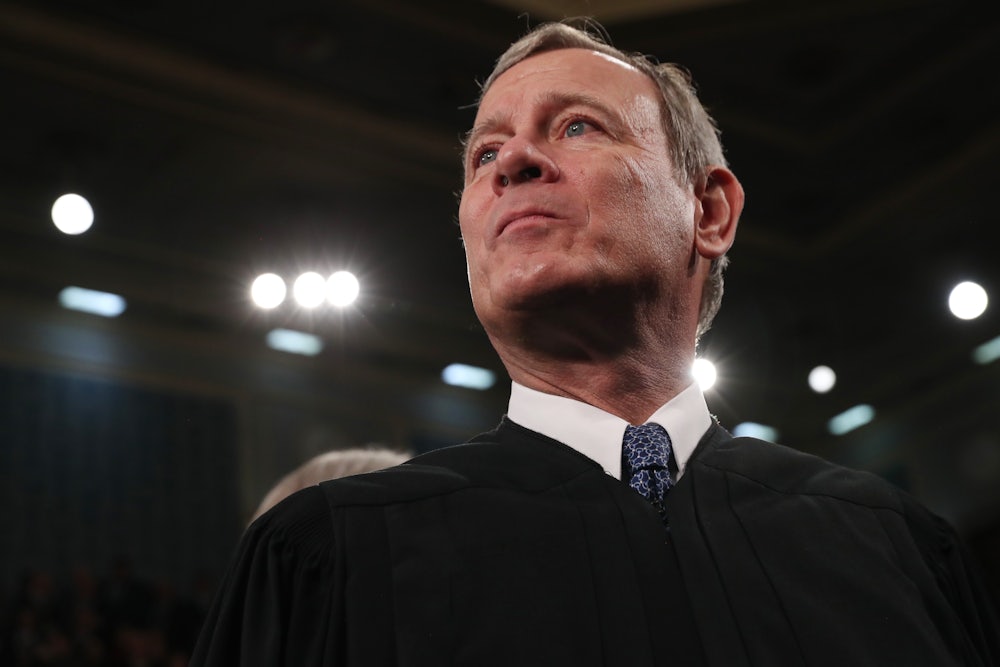

“Maine’s ‘nonsectarian’ requirement for its otherwise generally available tuition assistance payments violates the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment,” Chief Justice John Roberts wrote for the court. “Regardless of how the benefit and restriction are described, the program operates to identify and exclude otherwise eligible schools on the basis of their religious exercise.”

The decision comes as no surprise. Not only has the court reached similar decisions in recent years, but it also fits within the broader trend of extraordinary favoritism for religious freedom litigants before the Roberts court. Tuesday’s ruling also reflects an ongoing effort by the conservative justices to “clarify” the Establishment clause into abeyance, which could have serious consequences for Americans’ ability to keep the wall of separation between church and state intact.

Because of the dispersed nature of its rural communities, Maine does not operate public high schools in more than half of its school districts. The state fills that gap by compensating students who attend private secondary schools for the cost of their tuition in the districts where no public option exists. In addition to some other limiting factors, Maine required that the funds not go toward schools with a religious curriculum, citing its obligations under the Establishment clause.

Two sets of Christian parents sued Maine in 2018, however, arguing that the exclusion of religious schools from the tuition-assistance program violated the Free Exercise clause and other constitutional rights. “Absent the ‘nonsectarian’ requirement, the Carsons and the Nelsons would have asked their respective [school districts] to pay the tuition to send their children to BCS and Temple Academy, respectively,” Roberts noted. A federal district court rejected those claims under the existing precedents.

While the case went through the appellate process, however, those precedents had changed. The Supreme Court had taken two big steps toward opening the spigot of public funds to religious institutions. First, in Trinity Lutheran Church v. Comer in 2017, the justices struck down a Missouri policy that excluded religious organizations from a program that resurfaced playgrounds with recycled tires. Then, in Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue in 2020, the court struck down Montana’s “Blaine amendment,” a term for a common provision in state constitutions that generally forbids those states from using public funds for private religious education.

The Blaine amendments arose against a backdrop of anti-Catholic hostility in the mid-to-late nineteenth century. But other state constitutional provisions, including the ones at issue in Trinity Lutheran, sprang from a more generalized desire to avoid entangling state funds with private religious institutions. Those principles are deeply rooted in the American constitutional tradition. The Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, a disestablishmentarian law drafted by Thomas Jefferson and passed in 1786, declared “that no man shall be compelled to frequent or support any religious worship, place, or ministry whatsoever.”

The 1st Circuit Court of Appeals tried to distinguish the Supreme Court’s ruling in Espinoza from the facts in the Maine case. Roberts, writing for the majority, concluded that the lower court had erred in doing so. “Indeed, were we to accept Maine’s argument, our decision in Espinoza would be rendered essentially meaningless” because Montana could have achieved the same result by phrasing its ban differently, Roberts wrote. “But our holding in Espinoza turned on the substance of free exercise protections, not on the presence or absence of magic words.”

Justice Stephen Breyer, who had concurred with the conservative majority in the outcome of Trinity Lutheran, wrote in his dissenting opinion in Carson that the court had misread the relationship between the two First Amendment clauses. Citing other precedents, he referred to the idea that there is some “play in the joints” between them. “That ‘play’ gives states some degree of legislative leeway,” Breyer explained. “It sometimes allows a state to further antiestablishment interests by withholding aid from religious institutions without violating the Constitution’s protections for the free exercise of religion.”

In more immediate terms, however, Breyer warned of the societal consequences of the court’s ruling. He specifically described the “increased risk of religiously based social conflict when government promotes religion” in public schools. He noted, as one example, that both schools at issue in this case have policies that deny admission to students on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity, something that Maine lawmakers (and, likely, a good number of Mainers themselves) had opposed. “The nonsectarian requirement helped avoid this conflict—the precise kind of social conflict that the Religion Clauses themselves sought to avoid,” Breyer noted.

Ironically, it was Breyer who drew upon the Constitution’s original public meaning in this case more than the majority’s originalists. “People in our country adhere to a vast array of beliefs, ideals, and philosophies,” he explained. “And with greater religious diversity comes greater risk of religiously based strife, conflict, and social division. The Religion Clauses were written in part to help avoid that disunion.” In addition to citing Jefferson’s Virginia statute, he also quoted James Madison as claiming that “compelled taxpayer sponsorship of religion ‘is itself a signal of persecution,’ which ‘will destroy that moderation and harmony which the forbearance of our laws to intermeddle with religion, has produced amongst its several sects.’”

These warnings, both past and present, did not faze the conservative majority. “Justice Breyer stresses the importance of ‘government neutrality’ when it comes to religious matters, but there is nothing neutral about Maine’s program,” Roberts wrote for the court. “The state pays tuition for certain students at private schools—so long as the schools are not religious. That is discrimination against religion. A state’s antiestablishment interest does not justify enactments that exclude some members of the community from an otherwise generally available public benefit because of their religious exercise.”

In other words, when faced against each other, the Establishment clause must yield to the Free Exercise clause. Justice Sonia Sotomayor, who wrote a separate dissent, also noted that Tuesday’s decision effectively compels the states to fund religious schools with taxpayer dollars. Not so, claimed Roberts. The states, he argued, can just choose not to fund private education at all. “But once a state decides to do so, it cannot disqualify some private schools solely because they are religious,” he wrote, quoting from the court’s earlier decision in Espinoza. That will likely give little comfort to Maine lawmakers, who have effectively been told that they can stop subsidizing discriminatory policies only if they restructure their entire state’s education system.

This is not the only case where the Establishment clause may take a drubbing this term. In Kennedy v. Bremerton School District, one of the court’s still-pending decisions, a former high school football coach claimed his school district violated his free-exercise rights by firing him for praying at midfield with students after games. The district responded that it was bound to uphold the Establishment clause, which the coach had allegedly violated by implicitly pressuring students to pray with him.

At oral arguments in Kennedy last month, some of the court’s conservatives hinted that the case could be resolved by correcting the school’s supposed misinterpretation of that clause. Justices Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh both suggested that the court could disavow Lemon v. Kurtzman, an Establishment clause precedent that is no longer used by the Supreme Court but still remains on the books. Justice Amy Coney Barrett asked whether the court could find that the Establishment clause didn’t apply to the situation at all. Whatever path it takes, the court looks set to go even further to narrow that clause’s application in American life—and thus limit the tools that states and parents have to keep religious indoctrination out of public education.