The White House’s Slow Cease-Fire Shift Is Getting Tepid Reviews

Critics of the administration still feel it is falling short—but they believe the pressure they’re bringing is starting to be felt.

Over the weekend, Vice President Kamala Harris called for an “immediate cease-fire” in Gaza, and urged Israel to allow a greater flow of aid into the region. Harris called the situation in Gaza “devastating” and a “humanitarian catastrophe,” adding that “too many innocent Palestinians have been killed.”

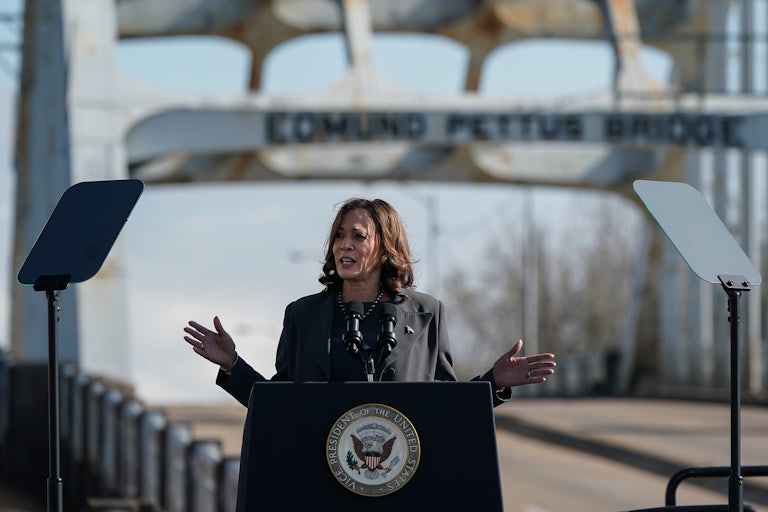

“Given the immense scale of suffering in Gaza, there must be an immediate cease-fire, for at least the next six weeks,” Harris said in remarks in Selma, Alabama, where her speech was frequently punctuated by applause and cheers.

Harris’s language was arguably more direct than any of the previous rhetoric that’s come out of the Biden administration, although her message was not a dramatic departure from the White House line. The White House has previously called for a six-week cessation in hostilities, and Harris urged Hamas—which she called a “brutal terrorist organization”—to accept a deal allowing for a cease-fire for the month of Ramadan, as well as a release of Israeli hostages. (NBC News reported that National Security Council officials toned down elements of Harris’s speech; the vice president’s office denies this.) The White House also authorized aid to be air-dropped into Gaza over the weekend.

Nevertheless, for critics of the Biden administration’s approach to the war in Gaza, a call for a temporary cease-fire doesn’t address one of their key demands: a reduction in America’s substantial financial support for Israel’s military campaign.

“Now they just have rebranded a humanitarian pause that they’ve always supported—a temporary humanitarian pause—as a cease-fire,” said Waleed Shahid, a progressive Democratic strategist who has previously worked with Senator Bernie Sanders and Representatives Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Summer Lee. “They’ve gotten comfortable with using that word that millions of people have been chanting around this country and the world, but the substance of the policy has not really changed that much, which is continued U.S. weapons funding for an operation that is indefensible.”

Layla Elabed, the campaign manager for Listen to Michigan—which urged tens of thousands of voters in Michigan to vote “uncommitted” in protest of the Biden administration’s response to the war in Gaza—said in a statement that Harris’s remarks were proof that “the Biden administration is moving because of the pressure from uncommitted Democrats.”

“But let’s be clear: This is a temporary cease-fire, or what they used to call a humanitarian pause,” Elabed continued. “Our movement’s demands have been clear: a lasting cease-fire and an end to U.S. funding for Israel’s war and occupation against the Palestinian people.”

Senator Chris Van Hollen, one of the members of Congress who has called for a cease-fire, said that he believed there is still more the Biden administration can do to put pressure on Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

“I think that it’s good that we’re doing airdrops, but airdrops do not begin to provide assistance at scale,” Van Hollen said. “The fact that the United States is doing airdrops is a clear symptom and sign of the fact that the Netanyahu government needs to be doing a lot more and the Biden administration needs to be pushing them to do a lot more.”

This week, Harris also met with a member of Israel’s war Cabinet, Benny Gantz, on Monday. According to Axios’s Barak Ravid, the meeting allowed for Harris and national security adviser Jake Sullivan to vent their frustration with the Israeli response to the October 7 Hamas attack, which killed more than 1,200 Israelis. Gantz, considered a political rival of Netanyahu, also met with Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries, and members of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. Gantz, whose visit to the U.S. was not approved by Netanyahu and has been controversial in Israel, did not meet with Speaker Mike Johnson.

“I thought he gave us reason to believe that our concerns should be Israel’s concerns in dealing with the humanitarian issues,” Senator Ben Cardin, the chair of the Foreign Relations Committee, told reporters after the meeting. “I think he heard that the situation should be a concern to all of us, to Americans and Israelis. We all have to deal with the fact that it’s unacceptable, and we all have a responsibility to respond to it.” (However, Cardin said that Gantz did not discuss a potential cease-fire.)

Harris’s remarks over the weekend are reflective of Biden’s need to maintain the support of certain key blocs of voters who traditionally vote Democratic.

“The fact that that speech was held in Selma gives me some indication that they see it as a broader problem with the Democratic electorate, including Black voters,” said Shahid. Last month, leaders of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, a prominent historically Black Christian denomination, called for an end to U.S. funding for Israel, citing the deaths of tens of thousands of Palestinians as “mass genocide.”

The location of her remarks was significant: She delivered them at the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, the site of a historic civil rights protest nearly 60 years ago this month. Representative Al Green, who has called for a cease-fire, acknowledged that the decision to give these remarks in Selma “could be a coincidence,” but he added that it could also be a sign that “we may be facing another Edmund Pettus Bridge moment.”

“I hope that we don’t have this Edmund Pettus Bridge moment where, in the month of Ramadan, we find ourselves with something very ugly happening in Gaza that could have been avoided,” Green told me. “I’m grateful that she made the call, and my hope is that we will heed her warning … in terms of lives being saved.”

This article first appeared in Inside Washington, a weekly TNR newsletter authored by staff writer Grace Segers. Sign up here.

Vibe Check: Shutdown week

The good news: The government probably isn’t going to shut down this weekend, the deadline for passing six appropriations bills. Lawmakers reached a deal to fund several agencies, creating a “minibus” of spending bills that will likely be approved in both chambers of Congress. This package includes measures to fund agencies covered by the Agriculture, Energy-Water, Military Construction-Veterans Affairs and Transportation-Housing, and Urban Development bills.

The bad news: As difficult as it was to reach an agreement on these bills, this is the easy part. The agencies funded by this minibus tend to be less controversial, although there were several minor sticking points that contributed to the delay in releasing these bills. (For example, whether to include extra funding for a nutrition assistance program aiding needy women and children, a provision that did make it into the final package.) The measures considered this week represent only around 30 percent of the discretionary spending to be approved this year.

It may be more difficult to reach a consensus on the remaining spending bills, which must be passed by March 22 to avert a shutdown. This minibus would include Defense, Labor-Health and Human Services-Education, Homeland Security, Financial Services, State-Foreign Operations and Legislative Branch measures. (Stop yawning! This is important!)

“It’s a lot of money, obviously. I think a lot of Democrats have a hard time sometimes with Defense, and some of our guys have a hard time with Labor-H,” said GOP Representative Tom Cole, using shorthand for the appropriations bills. However, he noted that when the two bills were paired in previous years, they ended up passing with more than 350 votes. They’ll need similarly large margins this year, as House leadership will use a procedural maneuver to put it on the floor without a formal vote in the Rules Committee, which will then require approval from two-thirds of the chamber.

Cole, who leads an appropriations subcommittee, also pushed back against some of the more far-right members of the Republican conference who have expressed frustration with the compromise funding bills, and with passing them as a group.

“You either govern, or you don’t. When you’re in the majority, you’re supposed to govern,” said Cole. “I regret that people think, ‘Well, I get to vote for defense and veterans, but then I don’t have to vote for anything else.’ Well, I’m sorry, but there’s a federal government out there.”

Hard-line conservatives are loath to accept that (a) the White House and Senate are held by Democrats and (b) Republicans have a razor-thin majority in the House, two factors that make it hard to contemplate passing appropriations legislation without the help of Democrats. After former Speaker Kevin McCarthy made a deal with Biden on government funding levels last spring, it became very difficult for current Speaker Mike Johnson to do anything but accept those numbers.

“We’re in a very difficult negotiating position right now, because of our thin margins and the fact that we’re having to do this under suspension,” said GOP Representative Steve Womack, referring to the floor procedure that will require the measure to receive two-thirds support on the House floor to pass.

“If [Johnson] is not going to get all of the Republicans to lock arms in supporting it, he’s going to have to raise the threshold and negotiate with Democrats,” continued Womack, the chair of the subcommittee overseeing the Financial Services appropriations bill.

Negotiations have largely moved past the subcommittee level, with final details being hashed out by congressional leadership. But this can cause frustration on both sides of the aisle, as rank-and-file members can be shut out from final talks.

“Republicans in the House basically refused to negotiate at the subcommittee level, so all of that is with leadership,” said Senator Chris Murphy, the chair of the appropriations subcommittee overseeing the Homeland Security measure, one of the thornier bills to negotiate.

But for the so-called appropriations “cardinals” leading the subcommittees, regardless of how difficult the second tranche of bills may be, it’s important to follow through.

When I asked Senator Jon Tester, the chair of the subcommittee overseeing defense appropriations, whether the next minibus would be more difficult to approve, he replied: “God, I hope not. I hope it’s easier.”

What I’m reading

Lauren Boebert doesn’t want to lose the House, by Ben Terris in The Washington Post

A lover of music, Hank Johnson’s newest mission is protecting hip-hop, by Tia Mitchell in The Atlanta Journal-Constitution

Joe Biden’s last campaign, by Evan Osnos in The New Yorker

Do Americans have a ‘collective amnesia’ about Donald Trump? by Jennifer Medina and Reid Epstein in The New York Times

Pet of the Week