Two recent opinion polls indicate that the American public is souring on the Supreme Court. Gallup’s long-running survey on the high court found that public approval of its actions had plunged to 40 percent, the lowest recorded level since it began asking the question in 2000. A separate Marquette University poll also found that 50 percent of Americans strongly or somewhat disapprove of the court’s rulings.

The shift comes after changes in the court’s membership and a summer of controversial, high-profile decisions. In the last four months alone, the court handed down major rulings on fully argued cases on religious freedom and voting rights as well as shadow-docket decisions on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s eviction moratorium, Texas’s de facto ban on most abortions, and college vaccine mandates. Some parts of the surveys suggest the ramped-up disfavor is due to a growing liberal alienation from the court after the Trump years. Other parts suggest that both right and left partisans are frustrated they each aren’t winning more often.

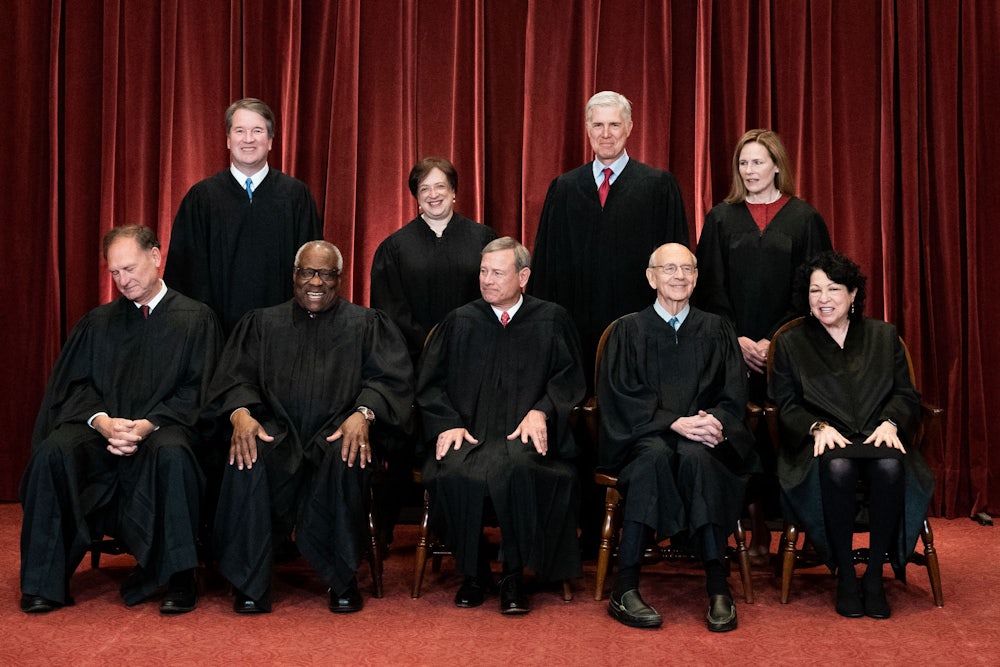

The justices, for their part, have only directly identified one possible culprit: the journalists who cover it. Justice Clarence Thomas complained earlier this month that the media “makes it sound as though you are just always going right to your personal preference” when ruling on cases. Justice Amy Coney Barrett expressed similar concerns in a Notre Dame speech the other week. “The media, along with hot takes on Twitter, report the results and decisions,” Barrett told the audience. “That makes the decision seem results-oriented. It leaves the reader to judge whether the court was right or wrong, based on whether she liked the results of the decision.”

I’ll avoid the merits of this particular argument since I’m obviously not a disinterested party, even though my own role is likely infinitesimal. But if the justices are frustrated with how the media is portraying their decisions to the public, they could always rethink how they actually communicate to the public themselves. The Supreme Court, both as a branch of government and as a group of nine federal employees, is extraordinarily bad at speaking to Americans. I cannot think of an institution in this country—whether it be civic, political, economic, social, religious, artistic, cultural, or otherwise—that is worse at it.

Imagine that you, a member of the public, are interested in following a specific case that the justices agreed to hear for oral arguments. You can read the filings for free on the Supreme Court website, but its docket navigation is so obtuse for nonpractitioners that you are better off looking it up on SCOTUSblog. (Good luck following the action in the lower courts, where actual money is required.) Would you like to see the oral arguments? You must attend them in person in Washington, D.C., because the court has steadfastly resisted cameras. If you wake up at the crack of dawn and stand in line for a few hours outside the building in the cold fall air, you might be lucky enough to get one of a handful of seats in the gallery. Alternatively, you can go to law school, practice appellate law for a few years, and become a member of the Supreme Court bar—they have their own seats.

Traveling to D.C. is not feasible for most Americans, of course, so what about just listening to the oral arguments? The Supreme Court recently adopted live audio feeds as an exigency during the Covid-19 pandemic, though it’s unclear if they’ll be a permanent addition. Prior to that, you would have had to wait until each Friday to listen to oral arguments from earlier in the week. Only in the most extraordinary of cases would it ever allow same-day audio releases, as in the Affordable Care Act disputes or the Obergefell ruling on marriage equality. If that doesn’t suffice, you can just wait a few hours for an 80-page transcript to be published somewhere on the court’s website. Good luck finding it.

What about the decision itself? In theory, the justices can and do make adjustments to their opinions until the moment they’re published, so the court doesn’t announce in advance when they’ll be handed down. You can see them handed down in person in D.C., but it’s roughly as laborious as seeing an oral argument, and there’s no guarantee of success. So you’re better off waiting for it to be posted online like everyone else. Recently the court began posting each day’s opinions on the front page of its website, but most Americans probably still prefer reading SCOTUSblog’s live blogs in order to try and make sense of what’s happening. That’s what famously happened in 2012, when even the Obama White House had to rely on SCOTUSblog to figure out whether its signature domestic achievement had been struck down.

Contrast this antiquated approach to transparency with just about any other government institution. Imagine if the National Weather Service announced severe-weather warnings in person at its headquarters, forbade journalists from filming or recording the forecasters’ statements, and then filed a written copy somewhere on its website for the public to find. Or if NASA didn’t provide updates on rocket launches until the astronauts made it back from space or weren’t coming back at all. Or if Congress turned off C-SPAN and released the minutes of its committee hearings a week after they happened.

Why is the Supreme Court so bad at this? Part of it seems to be inertia: The court gives special reverence to its traditional practices and tends to be averse to enacting new ones. Part of it may be practical, as well. Perhaps the justices are so focused on the litigants and lawyers who come before them that they take everyone else for granted. Other judicial bodies have a sharply different approach to public engagement. Anyone can watch livestreams of the British and Canadian counterparts to our own high court. I noted last year that many courts in the U.S. and overseas use Twitter to keep the public up to date on their workings to varying degrees. The Supreme Court is the only part of the federal government that doesn’t even bother to do the same. Even the CIA has a Twitter account.

It’s also worth noting that the justices themselves are rarely better at public engagement than the institution. Their public appearances are generally limited to law-school lectures or presentations to various legal groups, with reporters often forbidden from filming them. Unless they are part of book tours like the one Justice Stephen Breyer is currently on, the justices also almost never give interviews to print or broadcast journalists, even those who know better than to ask questions they won’t answer. If you were in high school when Chief Justice John Roberts joined the court in 2005, you probably never heard him say out loud more than the oath of office at presidential inaugurations before he presided over Trump’s first impeachment trial last year.

C-SPAN used to regularly survey the country for its views on the Supreme Court and the justices. Its poll found that at least half of Americans could not name a single justice from memory, with Ruth Bader Ginsburg only reaching 25 percent name recognition in the most recent survey in 2018. Those numbers are often used as a benchmark of Americans’ civic ignorance. But they may also reflect the justices’ failures to be known and understood by the American people on whose behalf they exercise the judicial power of the United States.

It goes without saying that the justices have obligations as judges not, say, to write newspaper op-eds about hot-button issues, or hobnob with people who have pending litigation before the court, or give freewheeling interviews on cable news about how they’ll decide future cases. No one can blame them for keeping a certain ethical distance from the ebb and flow of modern American life. I also don’t expect Justice Neil Gorsuch to start a podcast for movie reviews or Justice Sonia Sotomayor to offer baseball commentary on ESPN, as much as I might personally enjoy both of those things.

More substantive recommendations for rebuilding public support would likely fall on deaf ears. Though the justices’ docket is almost entirely discretionary, they are probably unlikely to heed warnings against making sweeping rulings on major social issues that could further alienate or inflame Americans, especially through the shadow docket. Thomas and Barrett also appear unconcerned that they’re undercutting their claims of nonpartisanship by simultaneously taking public victory laps with Mitch McConnell. But if the justices are so alarmed with how the public sees them, maybe they should rethink whether one of the most important parts of our constitutional system should be so needlessly opaque.