President Joe Biden received some blowback from liberals over the past week for a reported deal that he struck with Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell. Under the alleged terms of these strange bedfellows’ compact, Biden would nominate a specific candidate of McConnell’s choosing to a federal district court judgeship in McConnell’s home state of Kentucky. In exchange, McConnell would stop blocking two of Biden’s nominees for federal prosecutor positions in the state.

Judicial nomination bargains aren’t unheard of in the Senate, though this particular instance of favor trading does appear to be somewhat one-sided: It may be unprecedented to swap a lifetime judicial office for a four-to-eight-year position anywhere else in the federal government. To make matters worse for Biden, McConnell’s chosen nominee, Chad Meredith, has a notable track record of defending Kentucky’s anti-abortion laws in court. That makes it a strange choice on both appearance and substance—to say nothing of the timing. Emails obtained by The Washington Post indicate that the deal was finalized one day before the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade. (The Post reported on Wednesday evening that it was “unclear … whether the White House would ever move forward with nominating Meredith.)

But what caught my eye about their deal was the details of the judicial vacancy itself—namely, that it didn’t actually exist at the time these arrangements were fleshed out between Biden and McConnell. Meredith was set to be nominated for the seat that was held at the time by Judge Karen Kaye Caldwell, who was herself nominated to it by George W. Bush in 2001. Slate’s Mark Joseph Stern reported last week, citing sources within the Kentucky governor’s office, that Caldwell conditioned her retirement on the confirmation of a specific successor, who turned out to be Meredith.

This is as good a time as any to talk about strategic retirements in the federal judiciary and their implications. While no judge ever declares it outright, it’s common knowledge that many judges time their retirements to ensure that their successors will be chosen by a favorable president. This is why, for example, there was a small surge in retirements when Trump took office in 2017 as conservative judges who had outlasted the Obama administration chose that moment to depart. It’s also why the first year of Biden’s presidency saw a similar, albeit small, surge from liberal judges who didn’t want Donald Trump to choose their replacements.

Like many of our worst traditions, this one is bipartisan. A small army of liberal commentators openly urged Ruth Bader Ginsburg to retire during the Obama administration so that a younger successor could take her place, citing her longtime health struggles. Ginsburg declined, with dire consequences for the court’s long-term ideological balance when she was replaced by Amy Coney Barrett in 2020. Ginsburg’s longtime colleague Stephen Breyer, perhaps more cognizant of the risks if he did not step aside under a Democratic president and Senate, retired this year and was replaced by his former clerk, Ketanji Brown Jackson.

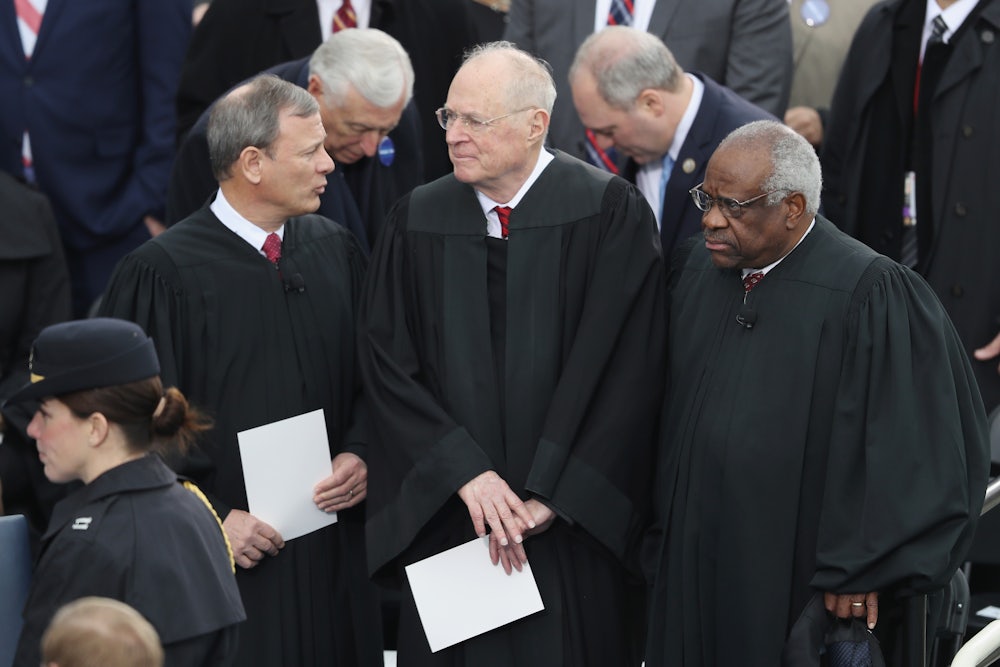

Conservatives also pulled off a monumental victory for their cause in 2018 when Anthony Kennedy, the court’s swing justice and its fifth vote to uphold Roe v. Wade, retired that summer. His replacement, Brett Kavanaugh, was one of Kennedy’s former clerks. The Trump administration took great pains behind the scenes to assure Kennedy that his legacy would be intact if he retired; by one account, Kennedy conditioned his retirement on Trump’s nomination of Kavanaugh to replace him. It may have been the most consequential deal that Trump ever made.

Conditioning one’s retirement from the federal bench on the Senate confirmation of a particular successor seems like the logical end point of this trend. It also risks creating what can only be described as a hereditary judiciary. By “hereditary,” I don’t mean that federal judgeships are literally passing from parent to child, of course. But the trend appears to be heading toward a place where federal judges arrange circumstances so they can effectively choose their own successors.

In fact, the last five or six years of Supreme Court confirmation battles might be better understood as a dynastic succession battle, akin to the wars that racked Europe in the early modern era. When Antonin Scalia suddenly died in the spring of 2016 under a Democratic presidency, it raised the prospect of the first 5–4 liberal majority on the Supreme Court since the 1960s. Republicans, who held the Senate at the time, refused to allow that possibility, and it fell to Obama’s successor, Donald Trump, to replace Scalia with a fellow conservative.

This is about as close as the United States, which has neither a monarchy nor a formal aristocracy, can come to something resembling hereditary government. Just as the choice of a Bourbon or a Habsburg monarch would define Spain in the eighteenth century, so too will the ideological balance of the Supreme Court chart most of the political landscape for Americans for the twenty-first century. It is no surprise that liberals still refer to the Scalia seat as “stolen” from them by Republicans—not in a literal sense, of course, but in the same way that Jacobites must have felt when the Stuarts were swept out of power in England’s Glorious Revolution.

It’s understandable to see the Trump-era Supreme Court justices as a natural outgrowth of the court’s existing conservatism. The Roberts court just got a little redder with Kavanaugh and then quite a lot redder with Barrett. But the successive replacement of three justices also represented the end of a constitutional era—a constitutional dynasty, perhaps—and the start of a new one. It’ll still be the Roberts court all along in the history books. It may be more accurate, however, to write of the end of the Kennedy court’s moderation and the start of the Thomas court’s dogmatism.

The problem with this state of affairs is that it’s unnatural. To whatever extent the Supreme Court ever has democratic legitimacy, the Thomas court is profoundly lacking in it. One-third of the court’s current justices, all of whom are in the usual majority, were chosen by a president who lost the popular vote. They were also confirmed by a Senate where the most votes and the most people does not equal the most seats. To compound matters, the court’s landmark decisions on abortion and gun rights are unpopular with the nation, and potential future rulings on marriage equality and contraception likely will be as well. Only 25 percent of Americans were willing to tell Gallup that they have confidence in the Supreme Court—an 11 percent drop from one year earlier and a historic low. The Supreme Court is not a democratic institution, of course. But even absolute monarchies try to avoid peasant uprisings.

There’s a way to fix this at the Supreme Court level. I’ve previously proposed that we expand the court’s size to 13 seats, with one seat for the chief justice and the other 12 seats assigned to the 12 federal circuit courts of appeal that have geographic jurisdictions. The associate justices would no longer be lifetime members of the court. Instead, when a vacancy arose for a particular seat, the next justice would be chosen at random from the judges within that seat’s respective circuit and serve an 18-year term.

When that 18-year term ended, the justice would then return to their previous role as a federal judge within that circuit. This would allow for term limits while preserving the independence that comes with life tenure. It would also prevent the elected branches from ideologically engineering the Supreme Court, which the conservative legal movement has done to tremendous effect in recent years. And it would reduce the incentives that lead to strategic retirements by the justices.

As for fixing this problem in the lower courts, the pathway for reform is less clear. The Constitution gives lifetime tenure to federal judges, and that can’t be legislated away. Impeachment also makes little sense as a solution in this context. That leaves a status quo in which certain portions of the federal bench become hereditary—not in the traditional sense but more akin to when Roman emperors would adopt their eventual successors. As long as Americans have reason to believe that certain federal judgeships belong to certain political factions—Democratic or Republican, Lancastrian or Yorkist—public confidence in the rule of law will continue to decline. And if there’s a truism to extract from our knowledge of hereditary rule, every decline eventually gives way to a fall.