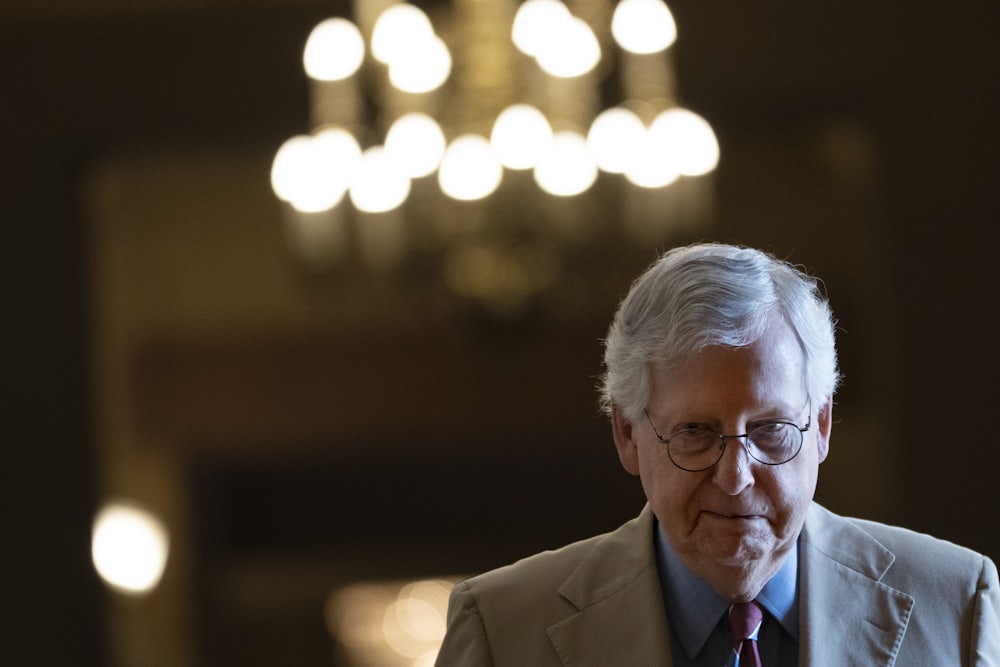

It’s a beguiling fantasy: Mitch McConnell lies bolt awake at 3 o’clock in the morning staring disconsolately at the ceiling. If you listen closely, you can hear him mutter, “Merrick Garland. Damn Merrick Garland. I should have confirmed Merrick Garland.”

It’s hard to imagine McConnell has much self-awareness beneath his carapace of complete cynicism. The Senate minority leader obviously blames Donald Trump for the loss of two Georgia Senate seats and a majority in January 2021. But in the deep dark night of the soul, McConnell should point to his own folly as the GOP’s chances of retaking the Senate in 2022 dwindle to 29 percent, according to FiveThirtyEight.

As Democrats remember with still smoldering fury, when McConnell was majority leader he refused to grant Garland even a token hearing after he was nominated to the Supreme Court by Barack Obama in March 2016 to fill the late Antonin Scalia’s seat. The day Garland was tapped, McConnell declared in the voice of the Senate undertaker, “It is a president’s constitutional right to nominate a Supreme Court justice, and it is the Senate’s constitutional right to act as a check on a president and withhold its consent.”

Nothing in McConnell’s long career—decades devoid of any principle beyond the pursuit of power—matches his refusal to consider a moderate Supreme Court nominee who was named almost seven months before the 2016 election. When Amy Coney Barrett was anointed by Trump to replace Ruth Bader Ginsberg little more than a month before the 2020 election, McConnell, with double-jointed flexibility, rubber-stamped her confirmation in a head-spinning 30 days.

What McConnell cared about was not social issues but creating a conservative Supreme Court that would tear down government regulations and rule the Republicans’ way on voting rights, gerrymandering, and campaign finance. Now McConnell has gotten the Supreme Court and the political blowback that he deserves as the abortion decision has mobilized Democratic voters and upended Republican hopes in November.

McConnell’s background suggests that he only cares about abortion as a box that all conservative Republicans need to check. According to Alec McGillis’s 2014 biography, The Cynic, McConnell was a staunch defender of abortion rights during his early career in local Kentucky politics. Only after McConnell was elected to the Senate in the 1984 Ronald Reagan landslide did he start staking out a hard-right position against Medicaid funding for abortion even in cases of rape and incest.

So when Barrett joined the court in late 2020, McConnell was probably reveling in his cleverness in thwarting the Democrats rather than thinking about abortion. Everyone knew that abortion decisions were in the legal pipeline, but the general expectation was that the conservative Supreme Court would continue to eviscerate Roe v. Wade piece by piece rather than reject it completely.

That was what would have happened if Chief Justice John Roberts were still the swing vote on a closely divided Supreme Court. As Roberts wrote with palpable frustration in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, “Both the Court’s opinion and the dissent display a relentless freedom from doubt on the legal issue that I cannot share.” If Roberts had been the author of the majority opinion, Mississippi would have been allowed to largely curtail access to abortion while Roe itself would technically still exist as precedent. But thanks to McConnell’s cynical machinations dating back to Garland, Roberts was a bystander as the other five Republican justices, led by a snarling Samuel Alito, handed down the most regressive Supreme Court decision in modern memory.

If Garland had been confirmed in 2016, this would have been the Roberts court instead of the Trump-McConnell Court. Had Roberts written the majority decision and avoided the outright disdain for Roe, Democrats would now be struggling to explain to wavering voters why the Supreme Court allowing Mississippi to go forward with a 15-week ban on abortion had such dire consequences. Instead, the dramatic repeal of Roe needs little explaining to anyone.

By every measure, Republicans are likely in trouble because the Alito opinion went off the rails. In almost every swing state, women are rushing to register to vote. Right-wing Senate candidates such as Blake Masters in Arizona have cleansed their campaign websites in a futile effort to hide their uncompromising anti-abortion views. This week, when Lindsey Graham proposed federal legislation banning abortion after 15 weeks, McConnell displayed visible irritation at the South Carolina Republican as he told reporters, “You’ll have to ask him about it.”

Once-vulnerable Democratic Senate incumbents have been buoyed by widespread public disapproval of the Supreme Court abortion decision. A prime example is Maggie Hassan in New Hampshire, a state where voters strongly support abortion rights. A mid-August poll by the St. Anselm College Survey Center found that 58 percent of voters oppose the abortion decision. And 50 percent of the electorate said that abortion is more likely to motivate them to vote.

This is Mitch McConnell’s legacy as he tries to become only the third senator in history* to regain the title of majority leader. If the 80-year-old McConnell fails in his quest in November, it will partly be because of his arrogance in rejecting Merrick Garland without a hearing in 2016. As the adage goes, “Revenge is a dish best served cold.”

* This article originally misstated the number of senators who have repeated as majority leader.