Last week’s inaugural banquet at the Executive Branch did not disappoint. The Executive Branch is an exclusive Georgetown club (initiation fee: $150,000 to $500,000) that Donald Trump Jr. co-founded to sell access to high-ranking Trump administration officials. Nobody ever accused the Trump family of being subtle.

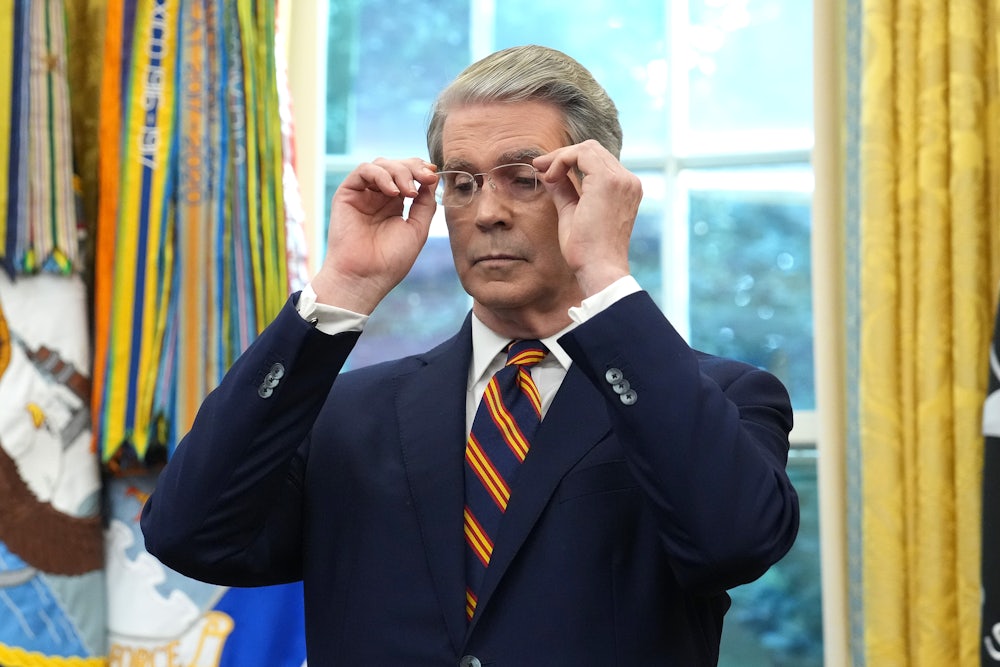

Among those present at the dinner were two of the Trump administration’s own cohort of nine billionaires (Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick and Small Business Administration chief Kelly Loeffler), plus the half-billionaire Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent and Federal Housing Finance Agency Director Bill Pulte, whose late grandfather was a billionaire. The highlight of this fancy soirée (crystal, china) occurred during cocktail hour, when Bessent said to Pulte: “I’m gonna punch you in your fucking face.”

This incident, first reported by Politico, attracted delighted press attention, with commentators noting this was the second time Bessent nearly popped a Trump administration rival in the snoot. The first was an altercation with Elon Musk in the West Wing in April, when Bessent went nose-to-nose with Musk and said, “Fuck you! Fuck you! Fuck you!” and Musk answered “I can’t hear you. Say it louder.” Bessent also told Lutnick, “Go fuck yourself” back in November when Lutnick tried to dislodge Bessent as President-elect Donald Trump’s choice for Treasury (and secure the job for himself). So far as we know, Bessent didn’t threaten to punch Lutnick, but that may be because it was a telephone conversation.

Bessent’s anger management challenges are wildly entertaining, and I yield to no one in my unseemly interest. But mostly lost in the gleeful coverage of the nearly thrown hands was the ultimate reason for Bessent’s bitter rivalry with Pulte, whose job title should rank him well below Bessent in the pecking order. The two men are locked in a dispute over who will control the planned privatization of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the two government-sponsored enterprises that back 70 percent of all U.S. mortgages. At the moment, Pulte is winning, and that pisses Bessent off. But the larger truth is that privatizing Fannie and Freddie would make mortgages costlier and benefit mainly a select group of wealthy investors—especially Trump’s new best friend Bill Ackman.

Yes, I’m afraid this is going to be an article about mortgage securitization. Before we get there, though, let’s review the good stuff—the tawdry details of last week’s near-fistfight.

According to Politico, Bessent said to Pulte as hors d’oeuvres were being served, “Why the fuck are you talking to the president about me? Fuck you! I’m gonna punch you in your fucking face.” Bessent then said to the club’s co-owner, Omeed Malik, “It’s either me or him. You tell me who’s getting the fuck out of here. Or, we could go outside.”

“To do what?” Pulte asked. “To talk?”

“No. I’m going to fucking beat your ass.”

It should be said in Bessent’s favor that he has good taste in enemies. Just as there were a lot of people inside and outside the administration who would have liked to fucking beat Musk’s ass when he was DOGE’s jefe, and who would still like to fucking beat Howard Lutnick’s ass, there are also a lot of people who would like to fucking beat Pulte’s ass.

It’s highly plausible that Pulte was talking shit about Bessent to Trump because Pulte talks shit about a lot of people to Trump, either directly or through his Twitter/X feed, which has three million followers. (Bessent has only 638,100.) Like Laura Loomer, Pulte appears to have adopted as his role model Madame Defarge, the vindictive informer who brings her knitting to beheadings in A Tale of Two Cities.

Pulte’s specialty is accusing Trump enemies of mortgage fraud for claiming in mortgage documents two or more residences as primary. (This is distinct from claiming in tax documents two or more residences as primary, a much more serious offense.) Pulte’s leveled this accusation at Democratic Senator Adam Schiff, New York Attorney General Letitia James, and Federal Reserve Governor Lisa Cook, in this last instance furnishing Trump with a phony justification to fire Cook for cause. All three deny the charges, and Cook remains at the Fed while she contests her dismissal in court.

“If somebody is claiming two primary residences,” Pulte has said, “that is not appropriate, and we will refer it for criminal investigation.” And indeed, the Justice Department is investigating Cook, James, and Schiff. But according to Reuters, only once in the past eight years has the federal government prosecuted this as a stand-alone offense. If it’s a fireable offense for Cook, ProPublica pointed out last week, then Trump is obliged also to fire three members of his Cabinet who did the same thing: Labor Secretary Lori Chavez-DeRemer, Transportation Secretary Sean Duffy, and Environmental Protection Agency Director Lee Zeldin. These three should also get criminal referrals to the Justice Department, along with Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton and Pulte’s own father and stepmother.

Maybe Pulte discovered a similar bêtise by Bessent and tattled privately to Trump (though if he did, ProPublica missed it). Or maybe Pulte bent Trump’s ear about Bessent’s failure thus far to honor his promise to the United States Office of Government Ethics to divest within 90 days from all his prior investments, which may violate conflict-of-interest laws. Or maybe Pulte echoed Paul Krugman’s and Jonathan Levin’s criticism that Bessent’s Wall Street Journal op-ed last week blaming the inflation run-up in 2021 and 2022 on the Fed’s quantitative easing a decade before made absolutely no sense. (No, wait, scratch this last, because the op-ed ran after the dinner.)

We don’t know whether or how Pulte bad-mouthed Bessent to Trump, but we do know why he might do so. The two are supposed to be working together on Trump’s promised plan to privatize Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the two big government entities that bundle mortgages into securities, and Bessent is getting in Pulte’s way.

The two have been at cross-purposes for some time. Soon after he assumed office, Pulte purged the boards of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac (among those let go were the Nobel laureate economist Simon Johnson) and appointed himself chairman of both. This week, Treasury and FHFA are holding competing roundtables on Fannie and Freddie, Joe Light of Barron’s reported Tuesday, in “attempts by both agencies to put their flags in the ground.”

Pulte wants to move fast to sell off a reported 5 percent of government-owned shares. This would generate a reported tens of billions in savings at a time when the multitrillion-dollar tax giveaway in Trump’s One Big Beautiful Act has the president searching under couch cushions for nickels. Bessent wants to move more cautiously, mindful that there are many moving parts and that a housing crisis (Bessent says Trump may declare it a national emergency) is an awkward time to fiddle with mortgage guarantees.

Wall Street isn’t persuaded that privatizing Fannie and Freddie is a good idea now or, possibly, ever. Privatization is, says a J.P. Morgan analysis, “a complex issue with significant risks and uncertain benefits.… Policymakers must carefully balance the desire to reduce government involvement with the need to maintain stability in the housing finance system.” Morgan Stanley is more bullish on privatization but advises “this process can’t be rushed” because Fannie and Freddie lack sufficient capital to go it alone and it’s doubtful an IPO would raise enough cash to make privatization feasible.

The truth is that privatizing Fannie and Freddie is, as noted by Bharat Ramamurti of the nonprofit American Economic Liberties Project, “a solution in search of a problem.” Fannie and Freddie are running quite well today—and certainly better than before the 2008 housing crisis, when they were private companies. Fannie and Freddie’s reckless investment in subprime mortgage–backed securities sent them into a tailspin, prompting Congress put them in conservatorship. Government ownership was no big deal, really; Fannie and Freddie, created by Congress in 1938 and 1970, respectively, have experimented with various structures over the years as public, semipublic, and private enterprises.

One large difficulty with privatizing Fannie and Freddie now is that for most of their existence there’s been some ambiguity about whether their securities were guaranteed by the federal government, signaling to the market at least a hint of moral hazard. The takeover in 2008 resolved that question: Yes, the feds guaranteed Fannie and Freddie’s solvency. If any doubt remained, Trump resolved that in May by shooting off his mouth on Truth Social that “I am working on TAKING THESE AMAZING COMPANIES PUBLIC, but I want to be clear, the U.S. Government will keep its implicit GUARANTEES.”

When you “make clear” that you’ll keep an “implicit guarantee,” then the guarantee is no longer implicit; it’s explicit. Which is fine if Fannie and Freddie remain part of the government, but not so fine if we invite private investors to assume full control of the company. As Bob Kuttner pointed out recently, that would be “privatizing speculative gain” and “socializing risk,” which gives you the worst of both worlds.

So why privatize these entities? As noted, Trump is desperate for revenue, and full privatization could gift the Treasury with an estimated $300 billion. The other reason, though, is that even in conservatorship Fannie and Freddie have issued some common stock, and their private investors are betting that the government will eventually relinquish ownership and make them rich.

Or, in the case of billionaire Bill Ackman, more rich. Ackman owns about 10 percent of this common stock—he calls it “a lottery ticket in the drawer”—and he’s the lead oligarch arguing for privatization. A week before the inauguration, he presented his own plan for privatizing Fannie and Freddie. He titled it “The Art of the Deal.” In it, Ackman argues, among other things, that the capital requirements for Fannie and Freddie are too high, which is what you’d expect someone to say about a pot of money that’s backed by the federal government.

The most interesting item in Ackman’s presentation, though, is a page that compares the return on the government’s bailout of Fannie and Freddie to the return on other government bailouts of private companies over the past couple of decades. “The government,” Ackman complains, “has already made more profit on [Fannie and Freddie] than all other bailout investments combined.” It’s true! AIG: 12 percent. GM: negative 21 percent. Fannie and Freddie: 57 percent.

To Ackman’s mind, this is terribly unfair. Why should the government extract so much more profit as the price of a bailout than it did for these other companies? But the flip side is that Fannie and Freddie have turned out to be fabulous investments for the U.S. taxpayer. And anyway, I thought Trump these days was all about government acquiring shares in private companies (U.S. Steel, Nvidia, MP Minerals, Intel), not selling them off.

Why on earth, apart from wanting to make Ackman wealthier still, would we get rid of these public investments in a garage sale?