For years, Facebook has had two sets of rules—if not more—for its users. One set applied to everyday people on its platform: your mom, your friend doing low-key MLM scams, that guy you knew in high school who got really into guns. While some of these regulations weren’t publicly shared—and may have varied between markets—others were more clear: prohibitions against hate speech, threats of violence, nudity. Violate them, and you were likely to be suspended or even banned, with little recourse. The other set of rules concerned the famous and powerful, especially politicians, who could do basically whatever they wanted.

Those separate systems of judgment are finally being folded into one, according to leaks emerging from Facebook, whose policy and enforcement mechanisms are often clouded in secrecy and opaque P.R.-speak. On Friday, according to The Verge, the company is announcing that the “newsworthy” test—the rules exception given to politicians if their posts are deemed to be a matter of public concern—is, if not going away entirely, at least being severely curtailed so that politicians’ posts will be judged by standards similar to those applied to your MAGA uncle in Ohio. It’s a decision that’s a long time coming, and it could be an important step in providing clearer, more unified speech standards on Facebook while also tamping down the unchecked power of politicians who use the platform to incite violence and spread disinformation.

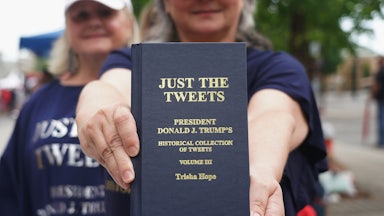

This expansive definition of newsworthiness—a presumption that even a politician’s incendiary posts should be allowed to go viral, to be used as a megaphone to weaponize speech, as if their very existence were deemed somehow in the public interest—was always full of hazard. It didn’t matter how many fact-checking notices were appended to a Donald Trump post; his words, and influence, still spread unabated. But Facebook’s policy was finally tested in a definitive way on January 6, when Trump’s speech on the Washington Mall, and some associated social media posts, encouraged hundreds of his supporters to march on the Capitol. After that, Facebook suspended Trump’s account indefinitely—or at least his access to it, as some posts remain up—a decision that was later affirmed by the company’s hand-picked oversight board. (Facebook later amended Trump’s suspension to two years.)

Despite this ostensibly egalitarian move of leveling the playing ground between the powerful and everyone else, there will be some differences, some unspecified leeway offered to political elites. “In the cases where an exception is made, the company will now disclose it publicly … after years of such decisions being closely held,” The Washington Post reported on Thursday. “And it will also become more transparent about its strikes system for people who violate its rules.” You may still not be able to appeal one of these “strikes” to an actual human being, but at least you’ll know you’ve got one on your record, and that perhaps your congressman does, too.

While Facebook’s content-moderation system remains a minefield of competing interests and unresolved, perhaps existential complications, this is a step in the right direction. Providing exceptions to politicians’ speech has placed them in a special, unaccountable class, where Facebook becomes less a news wire or RSS feed of political updates than a tool for propagandizing and incitement at scale. Facebook has faced scrutiny in a number of countries for how its platform has been used by governments to surveil and intimidate citizens, and BuzzFeed has reported how, here in the United States, right-wing pages received “preferential treatment” when it came to content moderation. From the allegiances of its corporate leadership to how its policy and moderation decisions are enforced, Facebook has always been a political actor, often exhibiting right-wing sympathies (a fact that’s become even more apparent as it’s emerged as a major lobbying force).

One recurrent problem in Facebook’s attempts to moderate content and enforce speech standards for a couple billion people hailing from 100-plus countries is that it’s enormously difficult to introduce nuance and calculated decision-making into the process. While statements by politicians might receive extended high-level attention, most moderation decisions are made within seconds, according to a restrictive rule book and sometimes without proper cultural context being available. (“Basically you get this lowest common denominator thing, which doesn’t make anybody happy,” Josh Sklar, a former content moderator for Accenture, a Facebook contractor, told me last month.) If politicians are now being judged by similar standards as ordinary users, then it’s within a system that experts have long said is crying out for reform and significant reinvestment.

By some conventional definitions of free speech, this policy shift represents an imposition on politicians’ speech rights. But massive digital platforms are not ordinary public squares, much less the equivalent of a presidential TV news conference. Rules, expectations, and cultural mores are still evolving in these spaces—with laws and regulatory measures flailing to catch up—but one thing is clear: Heads of state can use Facebook to exert profound influence in a way that goes beyond traditional notions of public speech. Trump’s noxious Facebook megaphone could not be countered with polite fact checks or “more and better speech,” as the truism goes. As a result, it received the response it deserved: Facebook shut down his broadcasting station. Whether Trump emerges elsewhere is up to him and his feckless team of enablers—his personal microblog has already ceased publishing, after little fanfare—but it’s no longer the job of Facebook. And that might be best for all of us.