Elon Musk’s New Threat Over Vegas Cybertruck Explosion Makes No Sense

How dare people report that a Cybertruck was involved in the Las Vegas Cybertruck explosion?

Elon Musk might be about to start suing any news outlet that fails to clarify that the Tesla Cybertruck that exploded in front of Trump International Hotel in Las Vegas this week did not simply explode, but rather contained exploding fireworks.

The billionaire technocrat was quick to clarify Wednesday that the car had not suffered a catastrophic malfunction.

“We have now confirmed that the explosion was caused by very large fireworks and/or a bomb carried in the bed of the rented Cybertruck and is unrelated to the vehicle itself,” Musk wrote on X. “All vehicle telemetry was positive at the time of the explosion.”

A few hours later, he weighed in on the media’s characterization of the so-called Cybertruck explosion, which documented, for all intents and purposes, a smoldering Cybertruck that had clearly experienced an explosion.

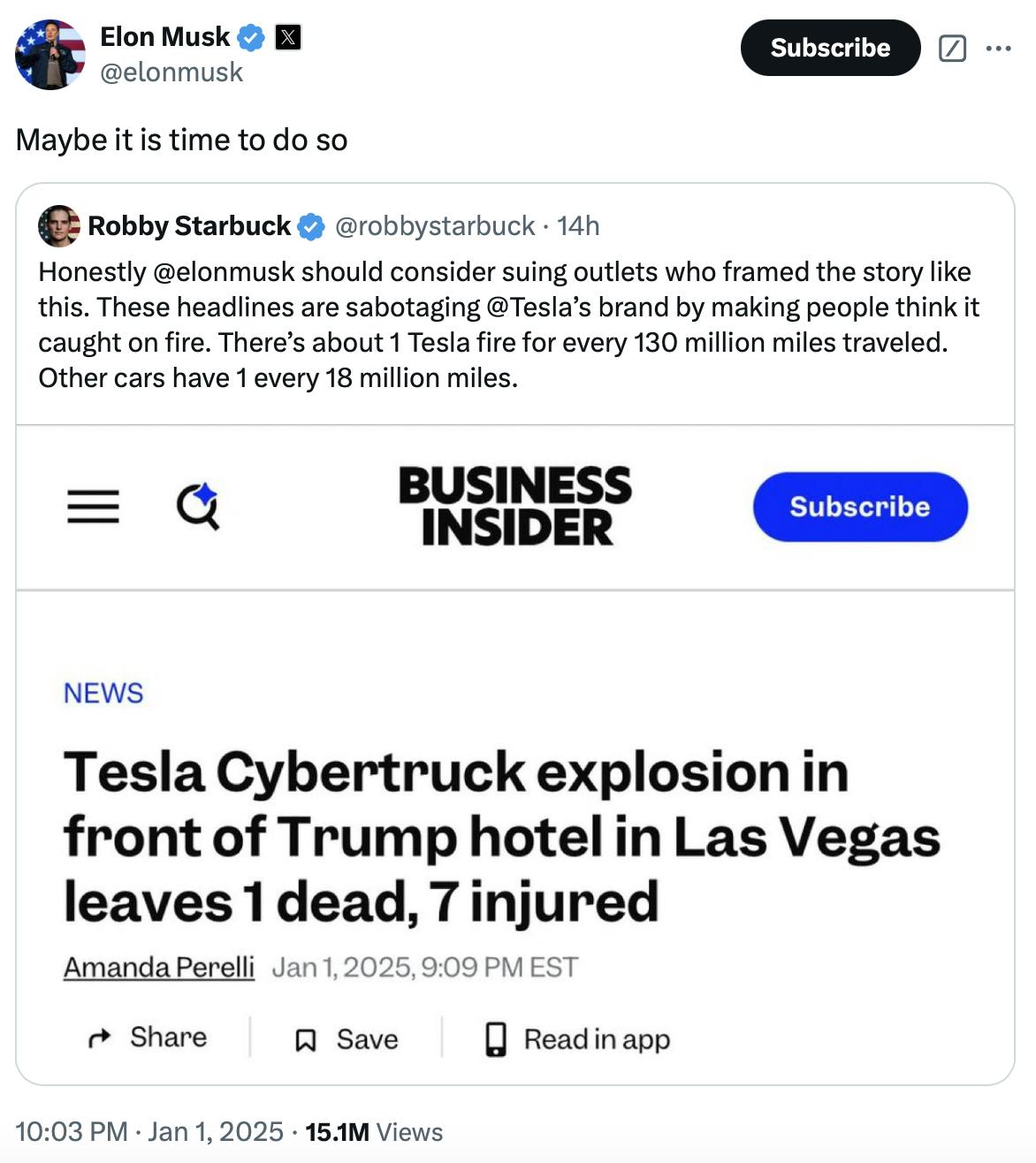

Anti-trans filmmaker Robby Starbuck posted on X lamenting the press’s coverage of the incident, suggesting that Musk ought to take legal action over headlines for simply using phrases such as “Tesla Cybertruck explosion,” without clarifying that the truck itself had not spontaneously exploded.

“Honestly @elonmusk should consider suing outlets who framed the story like this. These headlines are sabotaging @Tesla’s brand by making people think it caught on fire. There’s about 1 Tesla fire for every 130 million miles traveled. Other cars have 1 every 18 million miles,” Starbuck wrote, including a screen shot of a headline from Business Insider.

Musk reposted Starbuck, writing, “Maybe it is time to do so.”

The technocrat seems to be mulling whether to pick up a trick from his buddy Donald Trump, who has decided that he will sue any news outlet that says something he doesn’t like.

Starbuck and Musk are part of the same postliterate internet ecosystem built on reactionary responses to the headlines of articles users don’t actually bother to read. Lawsuits over the dispassionate, often 60-character, abbreviated versions of events that are later expanded upon in the body of the article simply suggest poor reading comprehension more than anything else.