Last fall, a parade of experts sized up President Joe Biden’s Covid testing mandate’s prospects before the Roberts court and deemed it good to go. The rule was “built on an extensive framework of legal public health and safety regulations,” said one report. Another said that “any lawsuit that may challenge a vaccine mandate” would be “frivolous” and “entirely unjustified.” Yet another report confidently positioned the verdict from legal experts: “Lawsuits and bans on mandates will largely prove fruitless because the law allows for such public safety measures.” Months later, the high court did what all the experts said could never be done and struck down the mandate. Legal expertise: What is it even good for?

But these experts were standing on some solid ground: The White House crafted the Occupational Safety and Health Administration rule with a 6–3 conservative court in mind. That is, as Matt Ford wrote for TNR at the time, it wasn’t really a vaccine mandate—it actually just required unvaccinated employees at workplaces under the rule’s aegis to receive Covid testing, while allowing the vaccinated to opt out. That placed the onus of demanding further from employees on their employers.

But much of the court’s reasoning for striking the OSHA rule down had little to do with what it actually said. In their decision, the conservative majority indulged in a lot of magical thinking about what constitutes a “work-related danger,” and concluded that spreading Covid-19 at work didn’t constitute one. Moreover, as Ford noted, the “majority read a requirement into the law that wasn’t actually there,” imputing an imaginary vaccine mandate into a regulation that bent over backward to exclude one. At one point, the majority concluded that it was “telling that OSHA, in its half century of existence, has never before adopted a broad public health regulation of this kind,” slamming the agency for the lack of historical precedent. OSHA could do nothing about this, as it didn’t exist during the 1918 Spanish flu epidemic.

The Atlantic’s Adam Serwer took a dim view of the politicized decision, tweeting, “There’s really no difference between Trump tweeting executive orders at his television while watching Fox News” and the majority opinion. The Daily Show’s Daniel Radosh added, “A lot of legal experts … gave assurances that Biden’s vaccine mandate was clearly allowed by law and precedent. If you haven’t yet figured out that this Supreme Court doesn’t care about those things, you are not a legal expert.” Their bafflement is understandable: It increasingly seems like the Supreme Court’s conservative majority is prepared to dispense with precedent and simply make up the rules as it goes along wherever ideological activism requires it, “originalism” and “textualism” be damned.

Naturally, the conservative legal movement spent decades investing in creating precisely this sort of court, so these decisions, and their underlying rationale, aren’t surprising. But there is a word for what the court’s doing: hackery. A Supreme Court that’s ready to steer headlong into hackery could have profound implications, not just for our politics, but for the practice of law itself. After all, the ambitious law students who aspire to argue before the Supreme Court have traditionally studied the high court’s decisions and precedents, the better to shape their argument. What’s the point in a world where the Supreme Court no longer values, well, the law?

But TNR contributor Simon Lazarus saw in the Supreme Court’s OSHA ruling a ray of hope that not all the conservative justices were ready to plunge headlong into hackery. While all six conservative justices agreed to strike down the rule, the conservative bloc split in its reasoning behind doing so. The opinion offered by Justices Roberts, Kavanaugh, and Barrett did apply “doctrinal and jurisprudential notions about how to interpret regulatory statutes,” Lazarus told me. It was simply their conclusion that was off, which “in my opinion, should not have barred OSHA’s rule as it was drafted.”

Perhaps the Supreme Court has not yet entered its Hack Era. But it still seems like we’re close. As TNR’s Alex Pareene wrote, back in October 2020, it would be gullible to think of Supreme Court justices as anything other than politicians themselves, regardless of their “just calling balls and strikes” pretensions.

And as The Atlantic’s Ronald Brownstein pointed out a few weeks ago, even John Roberts, the sainted institutionalist, has gone after voting rights with a zeal that verges on the political. Citing Harvard Law professor Nicholas Stephanopoulos, Brownstein notes that, “the Roberts Court has … never nullified a law making it harder to vote.” Meanwhile, it has nevertheless “nullified efforts to ensure voter access, combat gerrymanders, and to limit political contributions and spending.” Whether Roberts simply has naïve ideas about white racial innocence or has an active animus against nonconservatives voting, it’s tough to distinguish his actions from those of some political hack, simply hostile to the equal right to vote.

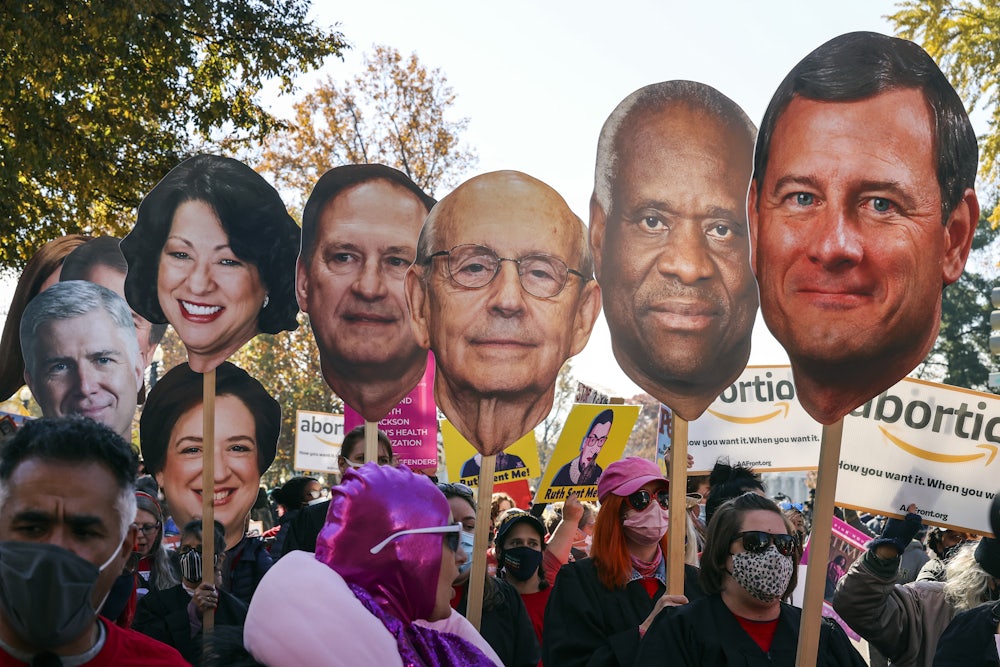

This Supreme Court has a blockbuster caseload before it this term; it’s likely that the United States will be a vastly different place by the time it ends. Perhaps some sense of decorum, respect for established precedent, and keeping with jurisprudential principles, will guide this court’s decisions. Or it may be that it will make up the rules as it goes, toss precedent into the wood chipper, and leave anguished attorneys desperately demanding, “Bro, do you even stare decisis?” As Bob Dylan once sang, “It’s not dark yet, but it’s getting there.”

This article first appeared in Power Mad, a weekly TNR newsletter authored by deputy editor Jason Linkins. Sign up here.