Trump Wants to Revive the Timber Industry—but Shot Himself in the Foot

Experts explain why the president’s plan to scale up production on federal lands will be hindered by his own administration.

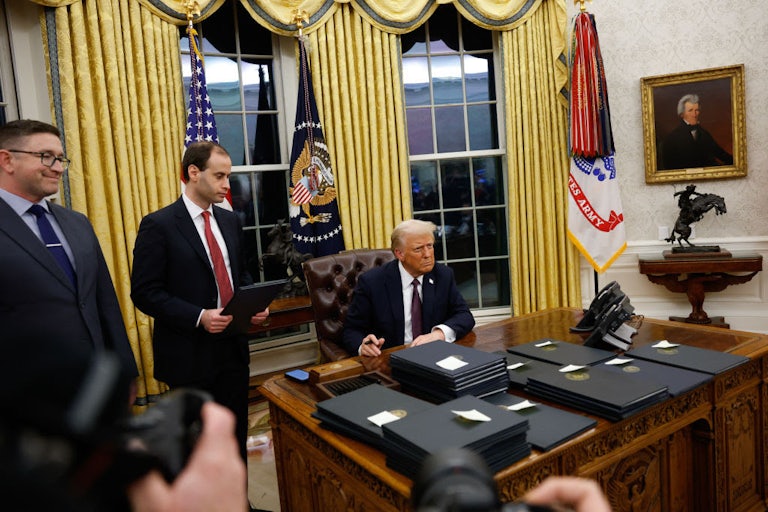

Days before new tariffs on Canada, Mexico, and China took effect earlier this month, President Trump issued two executive orders. One bemoaned America’s status as a net importer of lumber, ordering the secretary of commerce to investigate the “national security risks” of importing lumber and what would be needed for domestic production to fulfill all domestic demand. The other decried “onerous Federal policies” that have hampered the industry, directing the government to speed the approval of forestry projects on federal land and find ways to minimize the effect of the Endangered Species Act and National Environmental Policy Act.

Boosting logging is controversial from several angles. But as with many industries Trump claims to champion, there’s also a second question here: Is the administration’s theory of the industry’s decline—and prescription for its revival—actually accurate?

Trump’s tariffs and executive orders seem to assume that foreign competition and lack of lands to log are the primary things hampering U.S. timber production. But when I talked to experts familiar with the industry’s history, they painted a more complicated picture. There are some potential upsides to boosting domestic timber production—even on the environmental front. But the U.S. timber industry’s struggles aren’t as simple as the president seems to think, and some of his policies could even hurt the industry he claims to be helping.

Access to prime logging land “[is] really not the main factor holding things back,” said Michael Snyder, the former commissioner of Vermont Forests, Parks, and Recreation, who now consults on forestry and forest policy with Greenfire Enterprises. “Sure, increased supply of raw material … would seem on the surface to be helpful, but [it’s] not if you don’t have a workforce—that includes loggers, truckers in particular; if you don’t have receiving primary processing facilities, basic sawmills, secondary manufacturing facilities, retailers, and all of those elements of any value chain in the forest economy, which are all in distress right now pretty much everywhere.” Sawmills closing has been a problem for decades, and might not be an easy trend to reverse. “In Vermont, we’ve lost 158 mills since 2000, and I think last year Oregon lost seven major mills,” said Snyder.*

“There’s not one single factor that led to the decrease in both jobs as well as harvests,” said University of Oregon historian Steven Beda, who focuses on the history of the U.S. timber industry. Environmental backlash in the 1980s definitely had an effect in terms of limiting access to federal lands, he said. But also, the broader economic problems of the 1970s hit the industry hard, and over time traditional logging states like Oregon, Washington, and Idaho began to “pivot” from natural resource extraction “towards more of a high-tech economy,” said Beda, “so there’s less of an incentive for politicians to support the timber industry. Then you also have capital flight—a lot of the timber companies realizing that they can be more profitable operating in the South,” in part because of lower rates of unionization there. Both international competition and regional competition, he said, have played a role in reducing the size of the Northwest timber industry, which is the one Trump primarily seems to be targeting with his executive orders, since that’s where most of the federal forest land is located.

If the goal is to resurrect the pre-1980s Northwest timber industry, Beda said, that might be tough, because “both the workforce and the sawmills kind of stabilized and readjusted to the harvest rates that took shape after the end of the spotted owl conflict,” referring to the environmental backlash and endangered species advocacy that closed off many federal lands to logging.

Neither Beda nor Snyder see themselves as anti-timber. “I’m actually someone who believes that the Forest Service lands should be open to more logging,” said Beda. Snyder is a long-time advocate for people to value forestry more and take it seriously. “People realize they need plumbers and are willing to pay for it,” he said. “People don’t realize how much wood and wood products they use in their daily lives, from floors and cabinets to textiles and food additives and paper. They think we just need to leave forests alone. I don’t know where we’re going to get these materials. Plastics, concrete, and steel are far worse. So if not wood, what, and if not here, where?”

But both pointed to a serious problem with the Trump administration’s approach. It “just doesn’t add up,” said Snyder, pointing to the administration’s massive cuts across the Forest Service. “We’re going to get more wood off federal land but get rid of thousands of federal employees who actually do that work? It’s absurd.”

Beda agreed. “You can’t do both. You can’t cut Forest Service staff and say you want more logging on Forest Service lands. You need people to administer the contracts, put together the budgeting, all the zillion pieces that are part of public lands logging.… When you actually go back and look to the peak, the Forest Service harvests, at least in Oregon, peaked in the early 1980s, and that not coincidentally is also when the Forest Service had the largest budget and the largest staff.”

Tariffs could also hurt the industry long before they help because of the cross-border nature of wood processing. As the tariffs on Canada took effect, Snyder said, he heard from loggers in Vermont that their exports to the sawmills on the Canadian border immediately cratered. “Everything from up to a 50 percent price drop to complete shutoffs of deliveries. This is coming when we’re about to head into mud season, which is a traditional time for loggers to stay out of the woods ’cause of the vulnerable soft ground,” he said.

At the end of the day, “we should in my view be using more of our own wood, but these are not the buttons and levers to pull and push to get us there,” Snyder said. “It’s going to take an integrated, coherent, comprehensive approach.”

He’d like to see the Endangered Species Act protected, serious money put into research on sustainable forestry, how to preserve habitats and water quality, and whether wood products could substitute for things like single-use plastics and carbon-intensive construction materials like concrete. “The way we invest in high-tech, medical, automotive—we need to have the same kind of approach to the forests of our country and the people who manage and make their living in them,” he said. But “it’s not going to happen with sweeping executive orders and tariffs like this. It’s just going to piss everybody off.”

Stat of the Week

66%

That’s how many respondents support the U.S. transitioning to 100 percent clean energy by 2050, according to the Climate Opinion Maps that the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication recently published. (Also, 75 percent backed regulating carbon dioxide “as a pollutant” and 67 percent backed requiring fossil fuel companies to pay a carbon tax—striking numbers given that the Trump administration is moving in the exact opposite direction.)

What I’m Reading

‘Our people are hungry’: What federal food aid cuts mean in a warming world

Ayurella Horn-Muller and Naveena Sadasivam introduce readers to Mark Broyles, a 57-year-old living in Big Stone Gap, Virginia, where over 80 percent of residents voted for Donald Trump. Broyles’s “family of four, his mother, and her husband” have been using the food boxes provided by the nonprofit Appalachian Sustainable Development, which “helps small farmers sell fresh goods to public schools and grocery stores.” But now, due to Trump administration funding cuts, the food box program is gone. Programs benefiting both farmers and food-insecure households are folding across the country.

For decades, the USDA has funded several programs that are meant to address the country’s rising food-insecurity crisis—a problem that has only worsened as climate change has advanced, the COVID-19 pandemic led to layoffs, and grocery prices have skyrocketed. A network of nonprofit food banks, pantries, and hubs around the country rely extensively on government funding, particularly through the USDA. The Appalachian Sustainable Development is but one of them. The first few months of the Trump administration have plunged the USDA and its network of funding recipients into chaos.

The agency has abruptly canceled contracts with farmers and nonprofits, [frozen] funding for other long-running programs even as the courts have mandated that the Trump administration release funding, and fired thousands of employees, who were then temporarily reinstated as a result of a court order. Trump’s funding freeze and the USDA’s subsequent gutting of local food system programs has left them without a significant portion of their budgets, money they need to feed their communities. Experts say the administration’s move to axe these resources leaves the country’s first line of defense against the surging demand for hunger relief without enough supply.

Read Ayurella Horn-Muller and Naveena Sadasivam’s full report at Grist.

This article first appeared in Life in a Warming World, a weekly TNR newsletter authored by deputy editor Heather Souvaine Horn. Sign up here.

* This article originally misstated the state in which these mills were lost.