Snag Those Rebates for Home Energy Upgrades Before the GOP Kills Them

The Inflation Reduction Act’s incentives for buying, say, an energy-efficient boiler or water heater are safe—for now.

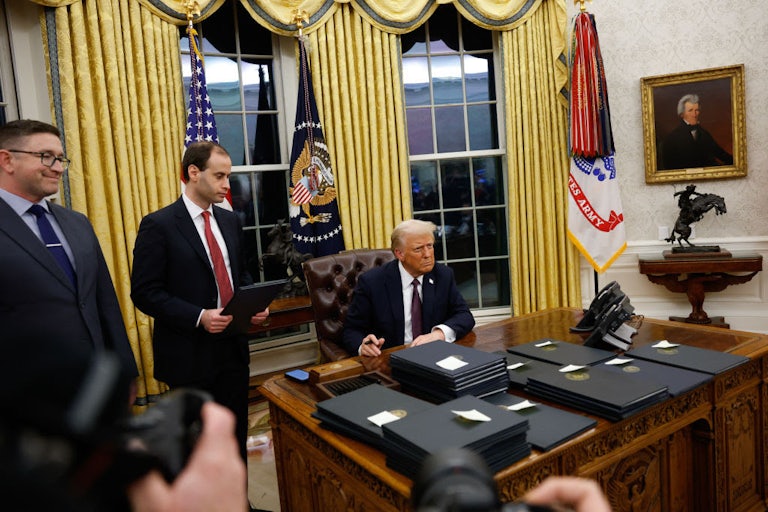

The Trump administration has disrupted quite a few money flows in its first two months, reserving special effort and scorn for those authorized by the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act. Farmers who undertook infrastructure improvements with the guarantee of Agriculture Department reimbursement suddenly found the payments frozen. Green banks, nonprofits, local governments, and other groups who had been awarded Environmental Protection Agency grants for everything from clean energy financing to lead pipe remediation found these grants “terminated.” The administration has even accused the grantees of fraud—though so far without much evidence.

This has startled people who thought you couldn’t legally cancel stuff that’s already been promised. Trump’s campaign pledge to rescind “unspent” IRA funds, it turns out, didn’t mean already committed funds were safe. Court rulings against the administration haven’t necessarily turned the taps back on. Nor, at the political level, has the IRA’s track record of benefiting red districts offered as much protection in these initial weeks as experts and advocates predicted it would; a congressional repeal effort is now underway, and while 21 House Republicans have said they oppose repealing the entirety of the act’s clean energy tax credits, their leaders show no sign of slowing their roll.

But let’s say you’re not a green bank or a farmer. Let’s say you’re not one of the groups currently suing the administration for breach of contract while the administration not-so-subtly threatens to sic the FBI on you for having the audacity to apply for and receive a government grant.

Let’s say you’re a homeowner whose boiler or water heater badly needs replacing, and you’re looking to defray some costs or even save on energy bills going forward. Let’s say your electrical panel is a growing fire hazard that you’ve ignored for way too long and the IRA’s provisions for panel upgrades could enable you to replace it. Do all those funds still exist? Or did you miss the window?

The incentives still exist, said David Friedman, senior director for federal policy at Rewiring America, a nonprofit focused on electrification. There are two main categories: tax credits, which get counted against your tax liability at tax time, and rebates, which can reduce up-front costs. The rebates, which the IRA stipulated had to be administered via state governments, “were a little more up in the air” for a bit, Friedman said. Only 10 states plus the District of Columbia had their programs up and running when Trump took office, and two of those paused them when the Energy Department suddenly froze the funds needed to reimburse states for the rebates. Now that the payment portal has reopened, The Washington Post recently reported, “some states, including California, New York, Maine and New Mexico, are continuing their rebate programs.”

Even if you live outside one of those states, the federal tax credits never went away. “It’s going to take an act of Congress to change that,” Friedman said. And even if Congress were to repeal this particular part of the IRA, “it’s pretty rare and honestly would be pretty painful to take away a tax credit in the middle of the year.… Typically when changes are made to tax law, it’s going forward, not present or going back.” If Congress were to repeal these, they’d probably just end them ahead of schedule—maybe by a few years, he said, or maybe in 2026, rather than cutting them midyear.

Tax credits don’t offer the instant affordability perks of rebates, of course. In the case of a new electrical panel or a heat pump water heater, the rebates could offer lower-income households $4,000 and $1,750, respectively, off the cost of the new devices, whereas the federal tax credit for a panel upgrade offers only 30 percent of the project cost, for a maximum of $600.

Rebates “help people who can least afford the skyrocketing energy prices people are facing today,” Friedman explained. “They’re targeted at low-and moderate-income households. These are folks who are much more likely to put a Band-Aid, effectively, on their hot water heater or their heating and cooling system because they can’t afford to repair it, and that traps them in an expensive cycle. It sticks them with an outdated unit that costs more to operate and so they have higher utility bills.” In theory, the rebate programs are set to expand, because every state except for South Dakota applied to participate in the program, Friedman said. Even states that don’t yet have their programs up and running have “got contracts with the money that is legally obligated to them.”

Contracts, of course, have not exactly deterred the Trump administration so far in its quest to freeze funds—despite a barrage of unfavorable judicial rulings. A growing number of advocates for these home energy incentives, though, are arguing that axing them would also be bad politics. “I think that one thing that’s become evident in the last year or so is that household energy costs—inflation, fossil fuel prices—those do seem to be more top of mind for Americans,” Energy Innovation senior director Robbie Orvis recently told Heatmap’s Matthew Zeitlin, in a piece about the “dollars-and-cents arguments” for keeping the IRA. Heatmap Pro’s own opinion modeling, Zeitlin noted, backed that up, showing that “lower utility bills is the number one perceived benefit of renewables in much of the country.”

“A package of heat pump, water heater, heat pump heating-cooling system, and some good insulation and windows is going to save you nearly a thousand dollars a year,” Friedman said. Getting rid of the incentives that make that more affordable for people, he said, “would be a tax hike on the American public. And at a time when you’ve got a president who’s promised to cut people’s energy bills in half, it would cripple their ability to fight high energy prices.” That’s in addition to Trump’s tariff policies possibly raising utility bills all on their own.

When analysts point out that IRA funds have particularly benefited red districts, they’re typically referring to money that has gone into manufacturing. But the home energy incentives could particularly benefit Republicans too. Homeowners are both more likely to lean GOP than Democrat and about twice as likely to self-identify as “strongly Republican” than renters are.

Whether either the manufacturing benefits or the utility-bill benefits to their constituents convince the GOP to spare the IRA remains to be seen. After all, lots of groups lean much further right than homeowners do; that hasn’t stopped Trump from pursuing policies that wreak havoc on their bottom lines.

Stat of the Week

26 gigawatts

That’s how much power—“more than the total generation capacity of most U.S. states,” Inside Climate News reports—it would take to clean up the wastewater from oil operations in Texas’s Permian Basin.

What I’m Reading

The Washington Post’s Allyson Chiu profiles Palava City in India, a newish experimental community where one study found that “maximum temperature is consistently 2 to 3 degrees Celsius (3.6 to 5.4 degrees Fahrenheit) cooler than in nearby cities, including Mumbai.” Low-energy cooling solutions are no small feat here, given that a lot of passive cooling strategies (like windcatchers) work better in drier climates. But buoyed by government support, high-income residents, and a more or less blank slate, developers are quickly throwing a lot of ideas on the table, Chiu reports. What they learn through trial and error, some hope, could help more traditional, cash-strapped cities:

Early apartments were built with smaller windows to reduce the amount of heat that could enter, Abdullah said. But when residents complained about the window size, he said, the developers responded by constructing apartments with larger windows set farther back into the building. This design provides shade and cuts the amount of direct heat hitting the glass. More recently, Abdullah said, they’ve been experimenting with glass treatments such as films that can be applied to windows to keep heat out.

On a sunny June day, the interior of a newly constructed unit with treated windows is noticeably cooler than the outdoors, even with the air conditioning shut off.

But window design is just one way the community saves energy. Palava has cut residential energy use through a combination of approaches, including installing solar-powered water heaters on buildings and efficient air conditioners inside.

Read Allyson Chiu’s full report at The Washington Post.

This article first appeared in Life in a Warming World, a weekly TNR newsletter authored by deputy editor Heather Souvaine Horn. Sign up here.