Trump’s EPA Head Has Learned One Terrible Lesson From Elon Musk

Lee Zeldin is taking a page out of the DOGE leader’s warped communications playbook.

In seven short weeks, the Trump administration has gone from promising a new “golden age” to arguing that a recession is “worth it.” It’s gone from promising “day one” egg-price decreases to telling people to “shut up” and keep backyard poultry. It’s gone from demonizing electric cars to advertising them on the White House lawn and characterizing Tesla protests as “domestic terrorism.” Most spectacularly, it’s gone from 25 percent tariffs on Mexico and Canada and 10 percent tariffs on China to a one-month pause on tariffs on Mexico and Canada, to 25 percent tariffs on Mexico and Canada and 20 percent tariffs on China, to a one-month delay on auto tariffs, to a temporary pause on tariffs on Canada and Mexico specifically for items compliant with the U.S.-Mexico-Canada free trade agreement, to a 50 percent tariff on Canadian steel and aluminum starting March 12 to … scratch that, never mind.

Perhaps you find this chaotic. Perhaps you think this administration lacks ideological coherence. That’s an understandable conclusion to draw, but it’s not the whole picture.

Several news stories this week suggest that the Trump administration not only has a few consistent positions but is starting to adopt a consistent communications strategy regarding those positions. One is that protest is illegal and protesters are terrorists. (These narratives have been on display both in the detention and attempted deportation of protest leader Mahmoud Khalil, and in Trump’s threat against Tesla protesters.) Another, which is now making its way into environmental and climate policy, is that extra-procedural cancellations of contractually or congressionally guaranteed payments are fine because they’re cracking down on fraud. And the common strategy in both these positions is to open with a bold assertion and, in lieu of producing evidence, escalate the assertions rapidly when challenged.

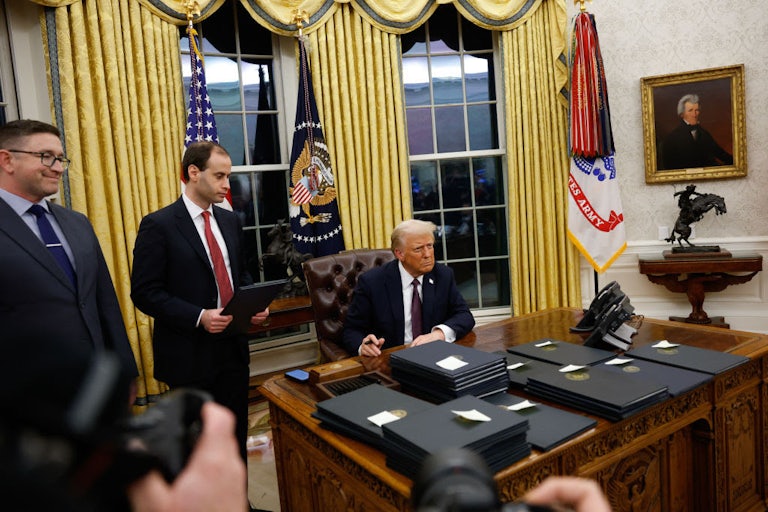

Elon Musk, the “special government employee” heading the newly created, legally embattled Department of Government Efficiency, has been refining this strategy for weeks. The dominant message from DOGE, initially, was that it was cutting down on government waste and inefficiency. A few weeks into the administration, as people began to question whether Musk and some random acolytes below the age of prefrontal cortex maturity should really be getting access to sensitive data, the fraud assertions started escalating. A day after a judge challenged the fraud claims, Musk and Trump held their joint Oval Office presser, on February 11, alleging “massive amounts of fraud,” “billions of dollars of abuse, incompetence, and corruption,” “foreign fraud rings” in “entitlement programs,” 150-year-old people receiving Social Security benefits, and “tens of billions of dollars” of positively identified fraudulent payments. (You can read The Washington Post’s debunking of this, and of the White House press secretary’s subsequent effort to substantiate these claims, here.)

Since then, these assertions have only grown in scale. On Monday, Musk told Fox Business’s Larry Kudlow that “entitlements” claims via fake or stolen Social Security numbers accounted for an estimated “10 percent of federal expenditures,” or “half a trillion dollars”—a staggering claim, which he then embroidered by claiming that the lure of this fast cash was a major contributor to undocumented immigration. (Half a trillion dollars, as Forbes reporter Alison Durkee pointed out, is about a third of total Social Security payments last year. Estimates from actual reports, with data, suggest less than 1 percent of Social Security claims are fraudulent. Musk’s claim that undocumented immigrants come to the U.S. to enrich themselves off Social Security is particularly bizarre, since undocumented immigrants are arguably the ones being scammed, paying into Social Security without getting anything back.)

Lee Zeldin, the Trump loyalist appointed to head the Environmental Protection Agency, seems to be following Musk’s lead. On Tuesday, he announced the termination of $20 billion in grants that have already been promised to institutions via the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund program, which Congress established in the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act. He cited “substantial concerns regarding program integrity, objections to the award process, programmatic fraud, waste, and abuse, and misalignment with the agency’s priorities,” but provided no evidence to support such widespread fraud claims. The best he came up with was that “a group linked to Stacey Abrams received two billion dollars after reporting a mere 100 dollars in total revenue the year before” (a debunking of which you can read here) and that “the founding director of the EPA’s program dished out $5 billion to his former employer.”

Pending clarity on the details, one could argue this last allegation is a conflict of interest—a weak one, given that the individual in question, Jahi Wise, doesn’t seem to have been rehired by that former employer—but not fraud, and not a conflict that can hold a candle to Musk, whose business has been built on an estimated $38 billion in government spending, being given the keys to the federal coffers and cutting subsidies to his flailing car company’s ascendant competitors. The press release also says the matter has been referred to the Office of the Inspector General and is being investigated by the Department of Justice and the FBI. In fact, a top DOJ prosecutor recently resigned after being asked to investigate EPA grants, reportedly declining to open a grand jury investigation due to insufficient evidence.

The Greenhouse Gas Reduction fund has elements that conservatives should celebrate: It aimed to reduce energy bills in cash-strapped locations, and to do so while minimizing government spending (by essentially using it only as seed money for private capital). But Zeldin, implementing Musk’s narrative strategy, has now turned the program into an increasingly colorful heist story. The administration’s crusade against it can be traced to a December video by right-wing sting group Project Veritas, in which a twentysomething EPA employee in the lame-duck Biden administration said that they were trying to get grants awarded as quickly as possible: “It truly like feels we’re on the Titanic and we’re throwing gold bars off the edge.” This isn’t really evidence of anything aside from a single twentysomething having a big mouth (and the analogy falls apart as soon as you think about it for more than two seconds). But as legal challenges to its extra-procedural spending freezes mounted, the Trump administration has clung to this analogy ever more closely. In recent statements, Zeldin has even adjusted his language in a way that implies his team has “located BILLIONS of dollars’ worth” of literal gold bars that the Biden administration tried to hide at Citibank.

Again: You may think this sounds chaotic. You may think that outlandish fantasies can’t be an actual comms strategy. But they are, and it’s not ineffective: The opposition can’t actually prove a negative, i.e., that fraud doesn’t exist, and if your team comes up with a wilder story each week, the press has to actually debunk it, which means they have to report that you said it, which means the claim itself is all that some people will hear or remember. Furthermore, the “fraud” story gives the Trump administration a victim to point to: you, the taxpayer. Any victim Democrats come up with therefore has to be more compelling to people than monetary self-interest.

The White House may be filled with people dressed in clown costumes throwing spaghetti at a wall. But they have a story about why they’re throwing spaghetti at the wall, and they’re sticking to it—and right-wing news networks are dutifully transmitting it to voters. If Democrats want to get a different message to voters, they’re not going to get anywhere by standing next to the clowns hurling spaghetti with a sign reading, “This is not normal.” Their only option is to go find some people who’ve been smacked in the face by projectile pasta, stick those people in front of a camera, and start making the case that the Trump administration is, in fact, hurting people.

Stat of the Week

22%

That’s how much the nation’s butterfly population has decreased in the last 20 years—a troubling indicator given insects’ foundational role in ecosystems.

What I’m Reading

What the world needs now is more fossil fuels, says Trump’s energy secretary

The Trump administration’s broader thesis on climate change is becoming clear. Speaking at the annual oil and gas conference known as CERAWeek, Energy Secretary Chris Wright, who earned $5.6 million helming a fracking company in 2023, outlined it: Climate change is happening, but it’s the necessary price you pay for the wealth that fossil fuel companies create. (The fact that fossil fuels create more wealth specifically for Wright and the other fossil fuel executives he was speaking to than they do for many of the people poisoned by them does not seem to have been discussed.) The Guardian’s Dharna Noor reports:

“The Trump administration will treat climate change for what it is, a global physical phenomenon that is a side-effect of building the modern world,” he added. “Everything in life involves trade-off.”

Though he admitted fossil fuels’ greenhouse gas emissions were warming the planet, he said “there is no physical way” solar, wind and batteries could replace the “myriad” uses of gas—something top experts dispute. Further, a bigger and more immediate problem was energy poverty, Wright said.

“Where is the Cop conference for this far more urgent global challenge,” he said, referring to the annual United Nations climate talks, known as the Conference of the Parties (Cop). “I look forward to working with all of you to better energize the world and fully unleash human potential.”

Read Dharna Noor’s full report at The Guardian.

This article first appeared in Life in a Warming World, a weekly TNR newsletter authored by deputy editor Heather Souvaine Horn. Sign up here.