How Safe Will We Be on Election Day?

As gun violence and political intimidation increasingly push into the public square, our polling places loom as vulnerable targets.

There was a sense in the days running up to the Independence Day holiday that something bad was brewing—that people just felt less safe. As Gothamist’s Matt Katz reported on July 2, New Yorkers were feeling apprehensive about being out in public because the prevalence of mass shootings in America was causing a similar prevalence of panic-inducing false reports of violence. As psychiatrist and sociologist Jonathan Metzl told Katz, it’s a problem that extends well beyond New York City: “I do feel like our entire country right now is traumatized by the fact that it feels like a mass shooting can happen anywhere at any time.”

Clearly, those fears were well founded: As CBS News reported, there were 11 mass shootings over the weekend, including the Highland Park shooting that claimed seven lives. In the wake of another fresh round of mayhem, the usual social media admonitions to get out and vote in the midterms circulated urgently—some more ham-fisted than others. These were of course followed by an equally robust fusillade of calls to do more than simply vote.

Obviously voting is an essential ingredient to political change. But a lot of politics happens between election days—something conservatives often seem to understand better than liberals. Still, for those hoping for high turnout, it’s worth asking: Will it actually be safe to go out and vote?

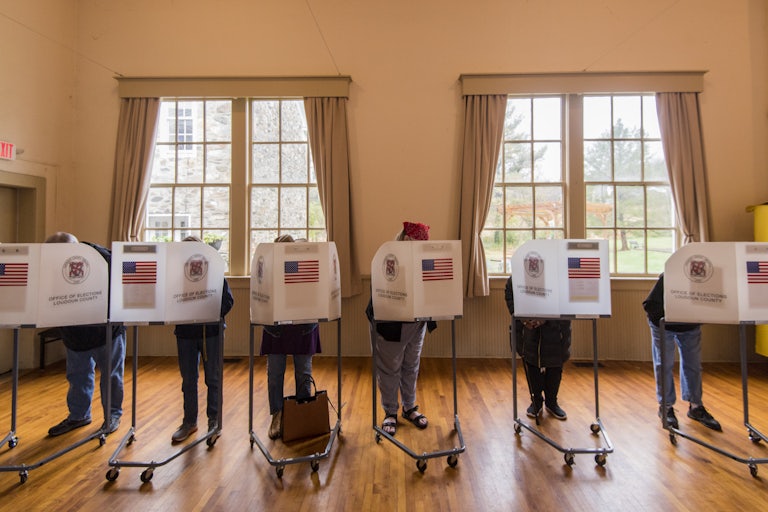

We live in an age when being out in the public square increasingly seems like a frightening prospect; it no longer feels like there’s safety in numbers. And standing in a line to vote at publicly demarcated polling places very much requires us to venture into a space that now feels vulnerable—where we might find ourselves under attack.

As Georgetown professor Heidi Li Feldman explained on Twitter, “Anti-democracy institutions and people” propagate fear and vulnerability by making “more guns available to more people”—the single condition that accounts for America’s unique problem with gun violence. “By making it dangerous for people of diverse backgrounds to gather in public, gun mongers promote fear and suspicion of one another,” Feldman notes. “By making public space so vulnerable to deadly violence, those who promote and push guns strike at the civil fabric.” What gets lost as that fabric frays is a sense of a “civil society” that we can all share.

And what we gain is more fear. As Amy Spitalnick, the executive director of Integrity First for America, points out: Sowing fear is “why mass shooters [and] extremists directly target public events—from neo-Nazis attacking Charlottesville community members who were protesting, to attacks on Pride events and abortion protests, to the targeting of public officials. The violence is key to undercutting democracy.”

As the right continues to plot its path toward permanent minority rule, it is making political violence more mainstream, alongside the GOP’s massive voter-suppression project. It’s hard to deny how violence has become an essential ingredient of the plot to deconstruct democracy. Since the 2020 election and the disputes that arose from President Donald Trump’s Big Lie, election workers have quit in droves because of the constant violent threats they receive. Two Georgia election workers, Ruby Freeman and Shaye Moss, recently provided harrowing details to the January 6 commission about the ways their lives were “upended” by a nonstop firehose of “harassment and racist threats.”

Meanwhile, right-wing militias that once vowed to “protect the polls” have only increased their presence in our politics and our civic life, where they’re massing in the public square and taking orders on who to intimidate. After the most recent evidence surfaced by the January 6 commission, it’s no longer hard to imagine such thugs receiving instructions from on high to shut down Democrat-heavy polling places by any means necessary.

Wasn’t the 2020 election supposed to be a rebuke of the culture of political violence Trump and his ilk famously promulgated? Apparently not: “Far from reducing violence, the 2020 election and its aftermath heralded a step-change in the mainstream acceptance of violence as a political tool,” writes Rachel Kleinfeld at Just Security. “Why would a faction of Republicans still in power or running for office at the federal, state, and local level make common cause with violent criminals? Because violence and intimidation are already bolstering their power.”

What is to be done? Unfortunately, we remain stuck in the “vote harder” endless loop; we aren’t likely to pass a law protecting voters at the polls, for the same reason we’ve not enacted any voter protections in spite of these threats to democracy—not enough Democrats believe these measures are more important than preserving the filibuster. Democrats who feel otherwise must elect additional senators who are willing to change these rules. To get there, Democratic voters must feel safe enough to go to their polling places, and cross their fingers that their votes get counted.

This might be one occasion when less skittish Democrats should try their luck at passing a bill to make our polling places safe, force Republicans to take a hard vote, and then get them to explain why the ostensible party of law and order opposes ensuring safety and security at the polls. If that’s the only thing that can be accomplished in the short term, Democrats can at least distinguish themselves as the guardians of stability in the public square, thus advancing the Good Life agenda in a small but meaningful way. And if something unthinkable happens on Election Day—well … we will at least be able to name and shame the lawmakers who enabled it.

This article first appeared in Power Mad, a weekly TNR newsletter authored by deputy editor Jason Linkins. Sign up here.