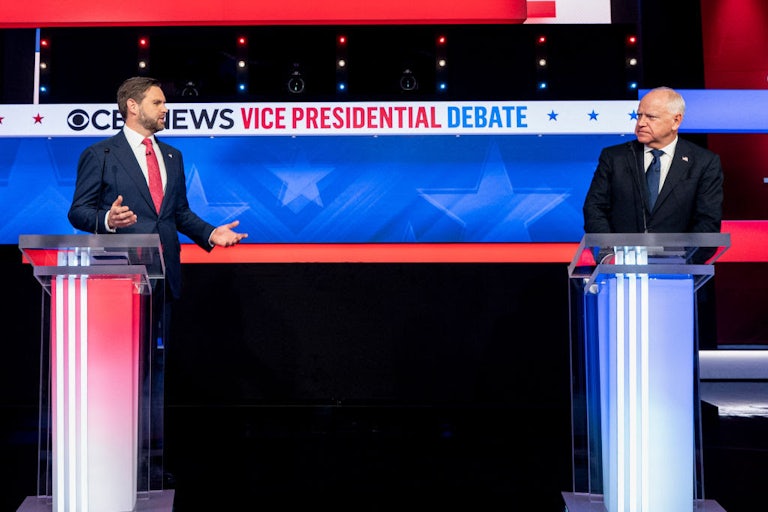

How Much Damage Can Lee Zeldin Do at the EPA?

Zeldin is a Trump loyalist, and Trump has already promised to gut any regulations that the oil industry doesn't like.

Donald Trump has named his pick to run the Environmental Protection Agency: Lee Zeldin, who was the U.S. representative for New York’s 1st congressional district from 2015 to 2023. What does that tell us about what lies ahead? The first thing to know is that Zeldin is about as natural a pick for EPA head as Martha Stewart would be for machinist’s mate on a nuclear submarine.

When Zeldin ran against Kathy Hochul for New York governor in 2022, he campaigned primarily on law and order, along with tax and regulation slashing, “ending all Covid-19 mandates,” and parents’ rights. He also has a long record opposing gay marriage and abortion. His environmental bona fides are mostly limited to having held an annual “Teach a Kid to Fish” day as a state senator and having been a member of minor congressional caucuses such as the Climate Solutions Caucus, the Congressional Estuary Caucus, and the somewhat questionable enterprise known as the Conservative Climate Caucus.

According to one Long Island politics expert I spoke to, Zeldin probably joined these caucuses just to appear responsive to voter concerns, given that Long Island Sound pollution is a big issue in Zeldin’s former district. The memberships did not translate to pro-environmental votes: The League of Conservation Voters gives Zeldin a lifetime score of 14 percent.*

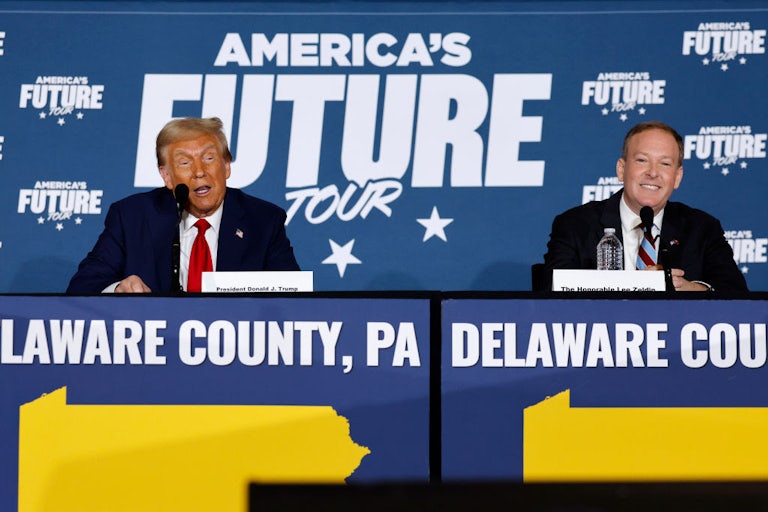

Zeldin is getting this job not because he’s interested in or qualified on environmental issues but because he’s a loyalist: He was one of Trump’s staunchest defenders in the first impeachment probe and one of four New York representatives to vote against certifying the 2020 election. At the Republican National Convention this summer, Zeldin sat in Trump’s own VIP box alongside members of Trump’s family and other cronies, only two seats away from the candidate.

“We will restore US energy dominance, revitalize our auto industry to bring back American jobs, and make the US the global leader of AI,” Zeldin promised on Monday—as if he’d been named energy or commerce secretary instead of EPA administrator. “We will do so while protecting access to clean air and water,” he added.

Unsurprisingly, environmental groups’ reactions to the pick have ranged from skeptical to outraged. On the one hand, it would be hard for Trump to do worse than his first EPA pick, Scott Pruitt, who was hired based on his experience relentlessly suing the EPA as Oklahoma’s attorney general. Pruitt resigned in 2018 amid an avalanche of ethics scandals that overshadowed even his abysmal policy proposals—like blocking the EPA from using public health research to show that pollution hurts people, repealing the Clean Power Plan, loosening fuel emissions standards, and much more. And Andrew Wheeler, who took over after Pruitt’s departure, was a former coal lobbyist.

On the other hand, the installation of a diehard Trump loyalist with little apparent agenda of his own suggests that the EPA is about to do precisely what Trump and his allies have been unusually explicit this time in promising it will do: please oil executives and, in former Interior Secretary David Bernhardt’s words, “rescind every one of Joe Biden’s industry-killing, job-killing, pro-China and anti-American electricity regulations.” (Biden was distinctly anti-China, and the oil industry kind of liked him—to climate activists’ chagrin—but whatever.) That’s in addition to likely decimating EPA staff, which the Biden administration had worked hard to rebuild after the last exodus.

Trump infamously promised oil executives last spring to reverse Biden-era environmental regulations in exchange for $1 billion in campaign contributions. Unsurprisingly, the oil and gas industry has compiled a wish list of regulations it wants axed. The American Exploration and Production Council, or AXPC, composed of oil and gas companies, is eager to repeal “more than a half-dozen executive orders that lie at the center of the Biden administration’s efforts to combat climate change,” The Washington Post reported last month, based on leaked documents. It is apparently fixated on getting rid of a new fee on excess methane released as a by-product of oil and gas production via flaring or leaks—a rule beloved by environmentalists because it reduces emissions of a particularly powerful greenhouse gas without actually requiring people to give up something meaningful. Meanwhile, the American Fuel and Petrochemical Manufacturers, environmental advocates told me, seem to be focusing on the EPA’s car emissions standards.

Zeldin will have the power to act on both of those—and many more. The vehicle standards could take some time, said Carrie Jenks, executive director of Harvard’s Environmental and Energy Law Program. That’s because that rule has already been finalized. “To roll back a final rule,” Jenks explained to me via email, “the Administrative Procedure Act requires an agency to propose a new rule, take public comment, and then finalize that new rule. The agency will have to explain what has changed and why, and the process of proposal, comment, and final rule takes agency resources and time.” That could take two to three years, she said, “and then any litigation starts once the rule is final.”

If the Trump administration haphazardly tries to rush the process, as it did during Trump’s first term, that might help environmental groups’ lawsuits to stop the new rules. The Natural Resources Defense Council has already pledged its readiness to challenge the Trump administration in court. During Trump’s last presidency, chief litigation officer Michael Wall said in a statement last week, “on average, we sued once every ten days for four years, and we won victories in nearly 90% of the resolved cases.”

The methane rule, formally known as the “waste emissions charge,” or WEC, could be reversed more quickly. Because it was only finalized on Tuesday, it’s vulnerable to the Congressional Review Act, which can be used to scrap a rule “finalized within 60 legislative days of the new administration taking office” via a simple congressional majority, Jenks explained. “We saw that used by the Trump administration last time as well as the Biden administration, and I would expect the Trump administration to consider where it can be used again.” Because the methane rule was mandated by the Inflation Reduction Act, “the EPA will continue to have the obligation to implement the WEC (through a different rule) until Congress repeals or alters the methane provisions of the IRA,” Jenks added. But “there are examples of where an agency fails to implement a rule, so that could also be a possible outcome.”

Then there are the rules that have been proposed but not yet finalized. Right now, several important ones fall into that category: proposed rules to limit industries’ ability to pollute the environment with harmful chemicals known as PFAS, for example. Proposed rules can be abandoned immediately. And a new rule for limiting greenhouse gas emissions from existing gas-fired plants, which was postponed while the administration finalized rules for existing coal-fired plants and new gas-fired plants, has not even been formally proposed yet. So that plan could be easily discarded, which is not ideal, given that gas-fired plants generate more electricity than any other type of plant in this country.

It would be a bit ironic if Zeldin were to scrap the PFAS rules—either the proposed ones or the one finalized this spring to reduce PFAS in drinking water. PFAS regulation is one of the very few environmental issues Zeldin repeatedly voted in favor of during his time in Congress: Twice he voted for a bill to require the EPA to set new drinking water standards and limit industrial PFAS discharge; he also voted for an amendment to the National Defense Authorization Act to set new standards for PFAS cleanups by the Department of Defense. But he also hasn’t been entirely consistent on this front, and at the end of the day, the point of appointing a loyalist is that they do what you tell them to. If Trump says to let industrial donors fill the nation’s waters with PFAS, it’s a good bet that Zeldin will do just that.

* This piece originally misstated Zeldin’s position on several congressional votes.

Good News/Bad News

![]()

The emerging consensus seems to be that Trump and a Republican Congress probably won’t repeal the Inflation Reduction Act (with its many clean energy incentives) in its entirety, because a lot of the money is going to red states. In other marginal good news, a billionaire’s effort to get rid of Washington state’s landmark climate law was roundly rejected at the ballot box, other states are gearing up to continue climate progress without the federal government, and the U.S. Air Force is walking back its initial claim that it doesn’t have to do anything to clean up the massive PFAS mess it created in Tucson, Arizona.

![]()

A different Washington ballot initiative, which aims to make it illegal for any municipality or the state itself ever to do anything that could be seen as discouraging gas energy or gas hookups in new buildings, looks like it’s going to pass. TNR’s Kate Aronoff wrote about the very weird background to that battle here.

Stat of the Week:

30 million tons

That’s how much ice the Greenland Ice Sheet is currently losing per hour, according to a new report.

What I’m Reading:

At Cop29, the Sun Sets on U.S. Leadership

This year’s international climate talks have kicked off amid news both of Donald Trump’s reelection as president of the United States and that 2024 is already a record-hot year for global temperatures. Despair and nihilism won’t help, but neither will sugarcoating the matter. So to that end, here’s Elizabeth Kolbert’s succinct summary:

In his first term, Trump withdrew the U.S. from the Paris Agreement. The day Biden took office, he moved to reënter the agreement. Trump in his second term almost certainly will withdraw from the accord once again. And it’s possible that the new Administration could take the even more radical step of withdrawing from the treaty that underlies the Paris Agreement, the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change, which was ratified by the U.S. Senate in 1992. Leaving the U.N.F.C.C.C. would make it virtually impossible for the country to rejoin because the move would require approval by two-thirds of the U.S. Senate.

Just how bad a second Trump Administration will be for domestic climate policy remains, of course, to be seen, but the most likely scenarios are all pretty bleak. During his first term, Trump tried to roll back more than a hundred environmental regulations. And, while the Biden Administration is rushing to try to “Trump-proof” various rules, including a set aimed at limiting oil drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, this seems unlikely to deter the incoming President, who, through his own nominees, has produced a U.S. Supreme Court deeply sympathetic to his agenda. According to a recent analysis by the British-based Web site Carbon Brief, were Trump to roll back the Biden Administration’s key climate initiatives, the U.S. could emit an extra four billion tons of CO2 by 2030. This, the analysis noted, “would negate—twice over—all of the savings from deploying wind, solar and other clean technologies around the world over the past five years.”

Read Elizabeth Kolbert’s full piece at The New Yorker.

This article first appeared in Life in a Warming World, a weekly TNR newsletter authored by deputy editor Heather Souvaine Horn. Sign up here.