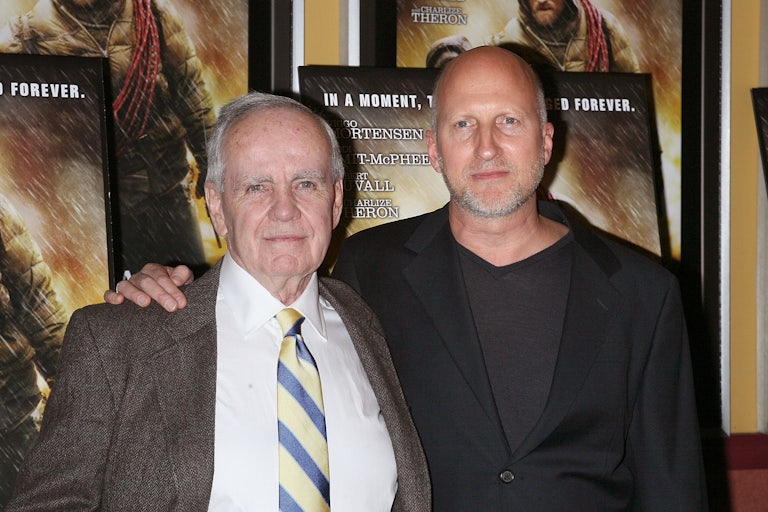

Cormac McCarthy, One of America’s Greatest Novelists, Has Died

He takes his place with Melville, Faulkner, and Twain in the pantheon.

No one wrote like Cormac McCarthy, who died on Tuesday in New Mexico at the age of 89. In the tributes and appreciations that will be published in the coming days, there will be mentions of Melville and Faulkner and maybe Twain. But McCarthy was an utterly singular and manifestly American writer, and a more than worthy heir to that triumvirate.

Much of that singularity was centered in McCarthy’s prose, which ricocheted—sometimes gracefully, sometimes jarringly—between gruff matter-of-factness and soaring, biblical grandiloquence. His style married Hemingwayean bluntness with the transcendent beauty (and sometimes ridiculousness) of the King James Bible. McCarthy’s passages—and his sentences, sometimes—merged the ordinary and the sublime. His novels frequently contained descriptions of extraordinary violence and gore, but they were rarely cartoonish, in part because of this ability to imbue the mundane with a prevailing, sometimes overwhelming sense of mystery.

McCarthy’s great theme was the frontier—a theme that was, arguably, the great theme of American culture for over a century. McCarthy wrote about the West, certainly, but also about life on the outskirts—my favorite novel of his is the hilarious, sad, autobiographical Suttree, which tracks life among vagrants and weirdos in Knoxville, Tennessee. McCarthy’s career began as the frontier’s central place in American culture was rapidly diminishing, and yet it’s notable in part because his work is strong argument for its continued relevance. For McCarthy, the frontier is where you go to understand America. Many of his best novels—Blood Meridian, No Country for Old Men, All the Pretty Horses—double as arguments for its continued relevance in American art.

McCarthy’s frontier was frequently a place of extreme violence and often evil, but it was also a place containing grand, if often inscrutable, truth and beauty. Much of McCarthy’s writing revolves around relatively straightforward themes—the nature of evil, the existence of God, the violence at the heart of America—but his characters frequently find themselves facing questions about the nature of existence itself.

Take the ending of The Road, McCarthy’s late-career postapocalyptic masterpiece:

Once there were brook trouts in the streams in the mountains. You could see them standing in the amber current where the white edges of their fins wimpled softly in the flow. They smelled of moss in your hand. Polished and muscular and torsional. On their backs were vermiculate patterns that were maps of the world in its becoming. Maps and mazes. Of a thing which could not be put back. Not be made right again. In the deep glens where they lived all things were older than man and they hummed of mystery.

Or this, from Blood Meridian:

The truth about the world, he said, is that anything is possible. Had you not seen it all from birth and thereby bled it of its strangeness it would appear to you for what it is, a hat trick in a medicine show, a fevered dream, a trance bepopulate with chimeras having neither analogue nor precedent, an itinerant carnival, a migratory tentshow whose ultimate destination after many a pitch in many a mudded field is unspeakable and calamitous beyond reckoning.

The universe is no narrow thing and the order within it is not constrained by any latitude in its conception to repeat what exists in one part in any other part. Even in this world more things exist without our knowledge than with it and the order in creation which you see is that which you have put there, like a string in a maze, so that you shall not lose your way. For existence has its own order and that no man’s mind can compass, that mind itself being but a fact among others.

At its best, McCarthy’s fiction could compass the strange and often violent order of existence. It is not at all clear that that order will ever find a chronicler of his manifold talents and complexity again.