Low Unemployment Is Good. Bank of America Disagrees.

Time to put the kibosh on all this corporate talk about how workers have to sacrifice their labor market leverage to fight inflation.

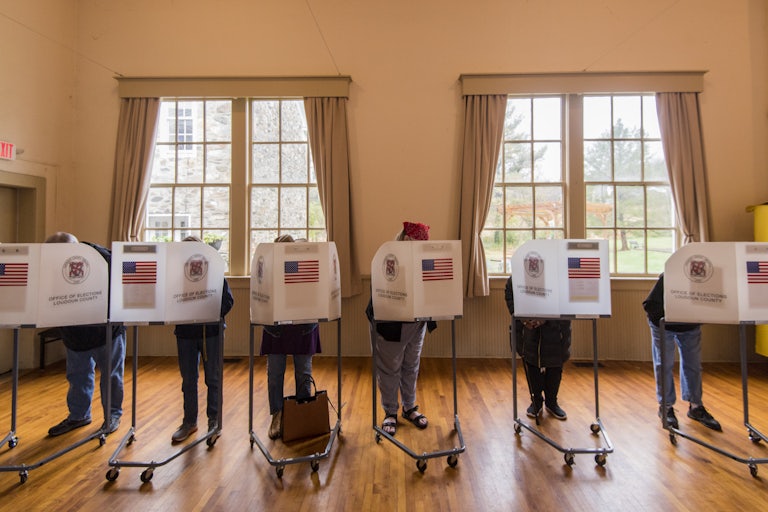

With a few months remaining before voters go to the polls for the midterm elections, no one should be under the illusion that the economy is offering Democrats many political advantages. Elites are arguing about whether we’re in a recession. Maybe we are, maybe we aren’t, but the very existence of that debate is not a great sign. Meanwhile, after a long period in which they didn’t seem to want to talk about inflation, beyond halfheartedly pinning the blame for it on Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the Democrats have only belatedly realized they can’t run from the issue and have renamed the Build Back Better Act as the Inflation Reduction Act (the bill itself got quite a reduction, too).

While these factors are far from ideal for Democrats, there are economic conditions worth highlighting—especially where the labor market is concerned. Federal fiscal relief helped engineer a swift recovery relative to the 2008 recession. The unemployment rate is low and employers are competing for talent rather than batting away job applicants. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, there are 0.6 unemployed persons per available job, which means there are about two job openings available for every unemployed person. And the recent boffo jobs report suggests that this part of the economy is still cooking with gas.

This is the sort of labor market that President Biden wanted to create, and for good reason: During his vice presidency, the Great Recession sent that ratio as high as 6.5 workers per job opening. It was a time of real despair for American workers, who largely shouldered the losses of Wall Street’s irresponsible gamblers. That workers took it on the chin was hardly celebrated as an act of patriotism. In fact, in the first midterm election after the recession began, the long-term unemployed were being regularly maligned by Republicans such as Senator Rand Paul, who on the campaign trail characterized the unemployed as people who needed to accept “a wage that’s less than we had at our previous job” in order to get off the dole. “Nobody likes that,” he said, “but it may be one of the tough love things that has to happen.”

And yet, here we are twelve years later, with workers off the dole and in jobs, and they’re still being maligned for their insufficient fealty to the demands of capital. Where their biggest sin was once nursing from the government teat, they’re now under the gun for coasting along in a market that’s suddenly become favorable to worker interests. The fact that workers might now be able to move more freely from a bad job to a better one, and command a better wage than they did at their previous place of employment, is somehow also seen as a problem in some quarters.

Last week, The Intercept’s Ken Klippenstein and Jon Schwarz obtained a private memorandum from a Bank of America executive who rather bluntly stated that his hopes that conditions for American workers might get materially worse.* The memo—which its author, Ethan Harris, characterized as a “mid-year review”—expressed grave concerns over the leverage that workers have at the moment. “By the end of next year,” Harris wrote, “we hope the ratio of job openings to unemployed is down to the more normal highs of the last business cycle”—that is, a ratio more conducive to employers having the leverage again.

As Klippenstein and Schwarz note, the memo “tells us what we suspected all along: The most powerful economic actors in the U.S.—entities like Bank of America and its clients—do not like working people to have power.” But this should probably come as no surprise: Intermittent presidential advisor and capital-class amanuensis Larry Summers has, in similar terms, endorsed the idea that American workers must give up their labor market gains in order to end inflation.

But in a speech during a recent conference on “Inclusive Populism,” author and TNR contributor Zach Carter was singularly unsparing in his critique of this anti-worker position:

Anyone who calls double-digit unemployment a solution to anything does not belong in politics. But the reasoning in play here should simply horrify people who believe in democracy. The most important cost-of-living issue for families this year is housing—in many cities, rent has exploded. Ask yourself: if the goal is lower rent, should we a) build more houses, or b) indiscriminately fire a large number of people from their jobs? The latter is the serious contention of this newly revived austerity brigade.

To contemplate engineering a spike in unemployment, at a moment where our republic is in genuine peril, is truly deranged. We need more stability and social cohesion right now, not less. And for the Democratic Party, which happens to be the only major party that wants to preserve the American experiment in multiracial democracy, there is a desperate need to connect better with voters outside of the affluent college-educated Americans they’ve already won over. They won’t get there if they allow workers to once again be thrown to the wolves without fighting for them.

More often than not, Biden’s age and experience is treated as a liability from the same pundit class that doesn’t seem to understand why it’s beneficial for workers to have the leverage they do. But it seems likely that a battle royale between labor and capital is starting to hover into view. Here, Biden’s belief that employers should compete for workers and his affinity for labor organizers is an example where his old-school thinking truly is aligned with our present needs. Taking up this fight may not save the Democrats’ bacon in the midterms, but there is another election just around the corner where victory may be even more necessary. Biden should go to any length to win it; his vision of a labor market that works for ordinary people will put him on favorable terrain.

This article first appeared in Power Mad, a weekly TNR newsletter authored by deputy editor Jason Linkins. Sign up here.

*This article originally reported that The Intercept was the first to report on the memo.